|

|

|

|

Wave-equation tomography by beam focusing |

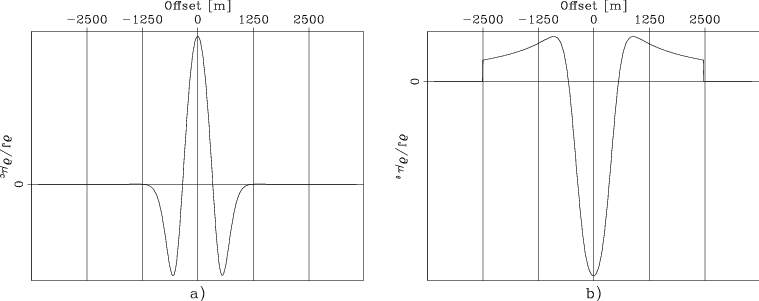

Similarly to Figure 3,

Figure 7,

shows the derivatives of the objective function

with respect to the moveout parameters computed using

equations 16-17

and 18-19.

The plot in panel a) displays the derivatives with respect

to the local curvature, ![]() ;

the plot in panel b) displays

the derivatives with respect to the time shifts of the beam centers,

;

the plot in panel b) displays

the derivatives with respect to the time shifts of the beam centers,

![]() .

In both cases the derivatives are plotted as a function of the

beam center coordinate,

.

In both cases the derivatives are plotted as a function of the

beam center coordinate,

![]() , for the source location at

, for the source location at

![]() km; that is, in the middle of the model.

As visible from the figure, I clipped to zero the derivatives

for both parameters outside

of the

km; that is, in the middle of the model.

As visible from the figure, I clipped to zero the derivatives

for both parameters outside

of the

![]() km range

to avoid edge effects.

km range

to avoid edge effects.

Figure 7a clearly shows that local curvature is not as an appropriate parameter for measuring the effects of small-scale velocity errors as it is for large-scale ones. The alternating signs of the objective-function derivatives causes the search direction to be highly oscillating as well. In contrast, the time-shifts derivatives shown in Figure 7b shows a large anomaly corresponding the localized velocity error and will provide useful slowness updates to localize the velocity anomaly.

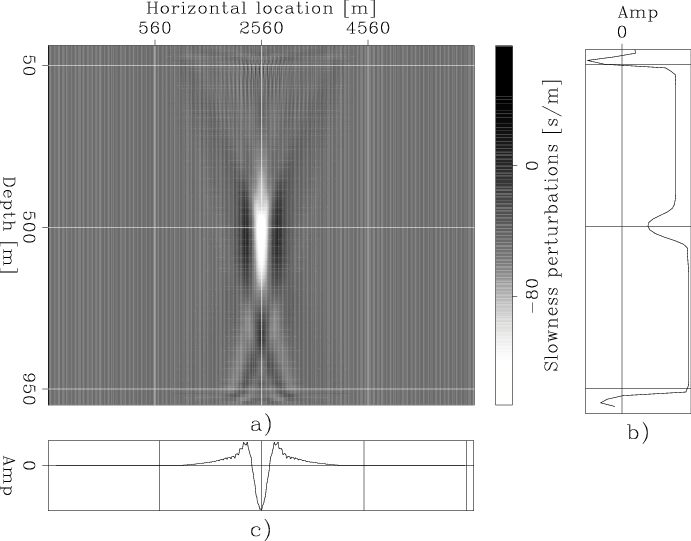

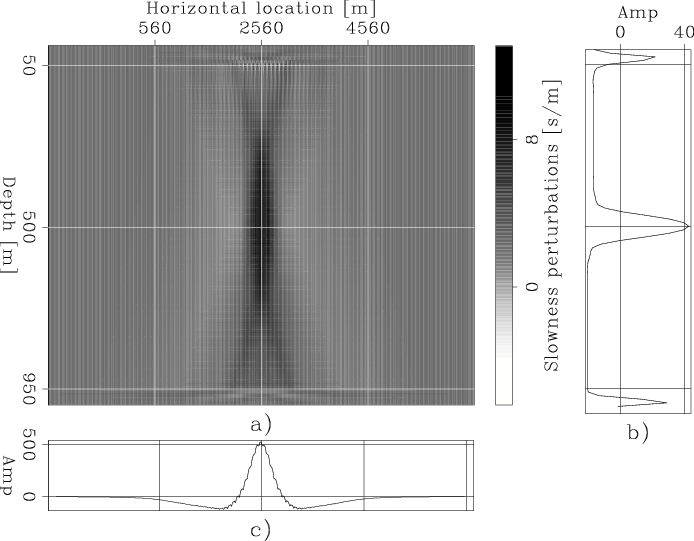

These observations are confirmed by Figure 8 and 9. Figure 8 shows the search direction computed using equation 24. As expected it oscillating around the velocity anomaly. Figure 9 shows instead a nicely localized anomaly with the correct sign. It is useful to notice that the horizontal averages of the search directions shown in Figure 8 and 9 have opposite polarity. The average of the search direction provided by the global component has the wrong polarity, except at the depth of the anomaly. Whereas the average of the search direction provided by the local component has the correct polarity. This observation confirms the analysis that local curvature carries more reliable information for the long-wavelength component of the velocity updates than the global time shifts, as observed when analyzing the uniform velocity error example.

Another interesting observation can be made by computing the ratio between the amplitudes of the slowness updates in the two cases. In the case of uniform error, the update computed from the local curvature is larger than the other by approximately a factor of 200. In contrast, in the case of the localized anomaly, the ratio between amplitudes is only about 10. This difference in relative amplitudes confirms that the two components of the objective function switch in relative importance between the two cases.

|

Beam-DC-DT-panom

Figure 7. Derivatives of the objective functions with respect to the moveout parameters plotted as a function of beam center coordinate, |

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

VH-Avg-Dir-Beam-panom

Figure 8. Search direction computed using the gradient of the local objective function |

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

VH-Avg-Dir-Glob-Beam-panom

Figure 9. Search direction computed using the gradient of the global objective function |

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Wave-equation tomography by beam focusing |