|

|

|

|

Wave-equation tomography by beam focusing |

To further simplify the theoretical development, I define an objective function that rewards consistency of the correlation computed independently for each source location. The objective function measures correlation consistency along the receiver axis. However, I use here the receiver axis as a proxy for the offset axis or the aperture-angle axis in reflection tomography. The application of the concepts developed in this paper to objective functions useful in reflection tomography should be straightforward, although it will require more complex notation and result in expressions for the gradients even more complex than the ones presented here.

I define the recorded data as

![]() ,

and the modeled data as

,

and the modeled data as

![]() ,

where

,

where ![]() is the recording time,

is the recording time,

![]() is the receiver coordinate,

is the receiver coordinate,

![]() is the source coordinate,

and

is the source coordinate,

and

![]() is the slowness model

defined in depth

is the slowness model

defined in depth ![]() and along

the horizontal coordinate

and along

the horizontal coordinate ![]() .

.

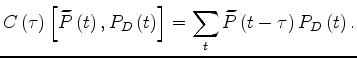

The cross-correlation

![]() between

the recorded data and the modeled data

is defined as a function of the correlation time lag

between

the recorded data and the modeled data

is defined as a function of the correlation time lag ![]() as

as

I introduce an objective function

that maximizes the flatness of the correlation function

along the receiver axis for all values of the lag ![]() .

In particular, I aim to maximize local correlation flatness

after subdividing the receiver array

into local subarrays.

To extract the correlation for each subarray

centered at

.

In particular, I aim to maximize local correlation flatness

after subdividing the receiver array

into local subarrays.

To extract the correlation for each subarray

centered at

,

I apply a local beam-decomposition

operators

,

I apply a local beam-decomposition

operators

![]() .

Within in each subarray,

traces are defined by the local offset

.

Within in each subarray,

traces are defined by the local offset

![]() .

The dimensions of each

.

The dimensions of each

![]() are thus

are thus

![]() .

.

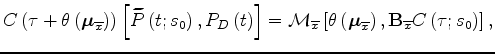

Given a background slowness ![]() we can compute the correlation

in equation 1.

In each subarray,

the correlation can be flattened

by the application of

we can compute the correlation

in equation 1.

In each subarray,

the correlation can be flattened

by the application of

![]() moveout operators

moveout operators

![]() ;

that is

;

that is

| (A-2) |

are the moveout parameters

and

are the moveout parameters

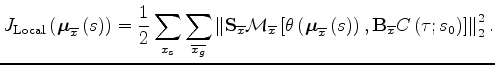

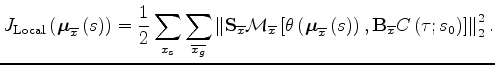

and I can now introduce the first, and local, term of the objective function that measures the flatness of the correlation within each subarray as:

,

but it depends indirectly from it through

the moveout parameters

,

but it depends indirectly from it through

the moveout parameters

.

These parameters are the solutions of

.

These parameters are the solutions of

and

and the moved-out correlation computed with the background slowness

and

and the moved-out correlation computed with the background slowness

For velocity estimation,

the most effective parametrization of the moveout within

each beam is the curvature ![]() ,

that defines the following moveout equation

,

that defines the following moveout equation

As the numerical examples I show in the next section demonstrate, the beam curvature is effective to capture the long-wavelength perturbations in the velocity model, but is less effective to capture the short-wavelength perturbations. Accordingly, a wave-equation tomography based solely on the objective function 3 may have difficulties to estimate short-wavelength velocity perturbations.

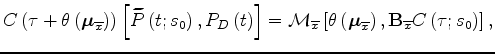

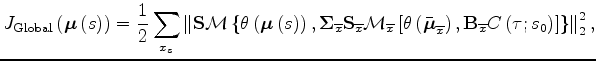

To address this shortcoming I introduce a second, and global, term to the objective function. This term measures flatness across the subarrays, after the local moveouts have been applied, and is defined as,

assembles all the results

of the stacking over the subarrays into a global array,

assembles all the results

of the stacking over the subarrays into a global array,

The global moveout parameters are the solutions of the following

![]() maximization problems

maximization problems

I chose to parametrize the global moveout

as simple time shifts for each beam center

![]() that is, the moveout equation is

that is, the moveout equation is

Combining the objective function in 3 and in 7 we define the maximization problem that we solve to estimate slowness:

|

|

|

|

Wave-equation tomography by beam focusing |