|

|

|

| Mechanics of stratified anisotropic poroelastic media |  |

![[pdf]](icons/pdf.png) |

Next: APPENDIX B: POROELASTIC FORMULAS

Up: Berryman: Stratified poroelastic rocks

Previous: SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

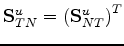

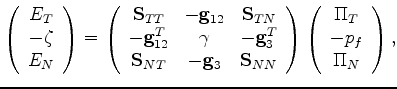

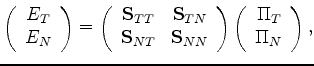

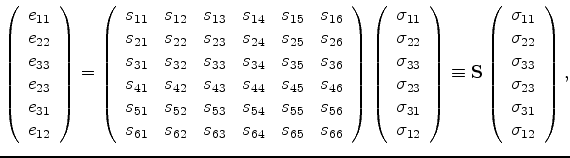

The quasi-static elasticity equations are

often written in compliance form using the Voigt  matrix

notation as:

matrix

notation as:

|

(40) |

where  is the symmetric

is the symmetric  compliance matrix.

The numbers 1,2,3 always indicate Cartesian axes (say,

compliance matrix.

The numbers 1,2,3 always indicate Cartesian axes (say,  ,

, ,

, respectively).

The

respectively).

The  -direction is usually chosen as the layering direction,

which could be oriented any direction in the earth.

But, in many geological and geophysical applications, the 3-axis (or

-direction is usually chosen as the layering direction,

which could be oriented any direction in the earth.

But, in many geological and geophysical applications, the 3-axis (or  -axis)

is also taken to be the vertical direction, and I conform to this convention here.

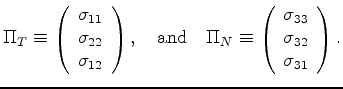

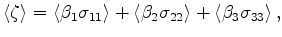

The principal stresses are

-axis)

is also taken to be the vertical direction, and I conform to this convention here.

The principal stresses are

,

,

,

,

,

in the directions 1,2,3, respectively. Similarly, the principal strains

are

,

in the directions 1,2,3, respectively. Similarly, the principal strains

are  ,

,  ,

,  .

The stresses

.

The stresses

,

,

,

,

are the torsional shear stresses,

associated with rotation-based strains around the 1, 2, or 3 axes, respectively.

The corresponding torsional strains are

are the torsional shear stresses,

associated with rotation-based strains around the 1, 2, or 3 axes, respectively.

The corresponding torsional strains are  ,

,  , and

, and

, where the torsional motion is again a rotational straining motion around the

1, 2, or 3 axes.

The compliance matrix is symmetric, so

, where the torsional motion is again a rotational straining motion around the

1, 2, or 3 axes.

The compliance matrix is symmetric, so

, and this fact

could have been used when displaying the matrix.

The axis pairs in the subscripts

, and this fact

could have been used when displaying the matrix.

The axis pairs in the subscripts  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  ,

are often labelled (again following the conventions of Voigt) as 1,2,3,4,5,6, respectively.

,

are often labelled (again following the conventions of Voigt) as 1,2,3,4,5,6, respectively.

The important contribution made by Backus (1962) [also see Postma (1955)]

is the observation that, in a horizontally layered system, there are certain strains

and stresses

and stresses

that are necessarily continuous

across boundaries between layers, while the others are not necessarily continuous.

I have been implicitly (and now explicitly by calling this fact out) assuming

that the interfaces between layers are in welded contact,

which means practically that the in-plane strains are always continuous:

so if axis 3 (or

that are necessarily continuous

across boundaries between layers, while the others are not necessarily continuous.

I have been implicitly (and now explicitly by calling this fact out) assuming

that the interfaces between layers are in welded contact,

which means practically that the in-plane strains are always continuous:

so if axis 3 (or  ) is the symmetry axis

(as is most often chosen for our layering problem), I have

) is the symmetry axis

(as is most often chosen for our layering problem), I have  ,

,

, and

, and  are all continuous.

Similarly, in welded contact, I must have continuity of the all the

stresses involving the 3 (or

are all continuous.

Similarly, in welded contact, I must have continuity of the all the

stresses involving the 3 (or  ) direction: so

) direction: so

,

,

, and

, and

must all be continuous.

must all be continuous.

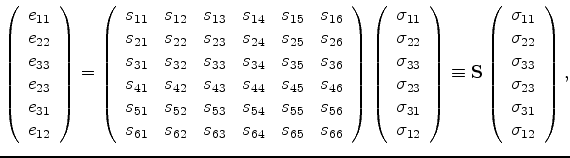

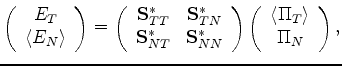

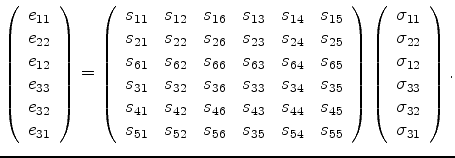

Then, following Backus (1962) and/or Schoenberg and Muir (1989) but -- for present purposes considering instead the compliance (inverse of stiffness) matrix --

I have rearranged the statement of the problem so that:

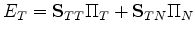

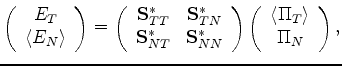

|

(41) |

Note that this equation, although similar to (40) is

nevertheless quite different because of the rearrangement of

the matrix elements and the reordering of the strains and stresses.

The expression in (41) is general for all elastic media.

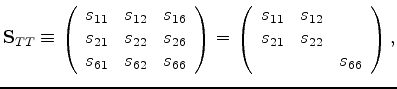

In the main text I restrict the discussion to orthotropic media. Assuming then that

I am using the correct set of axes as the symmetry axes in the presentation,

all off-diagonal compliances having subscripts  ,

,  , or

, or  in (40)

vanish identically. The diagonal shear compliances

in (40)

vanish identically. The diagonal shear compliances  , etc., generally do not vanish however.

, etc., generally do not vanish however.

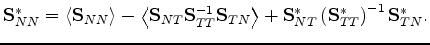

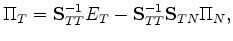

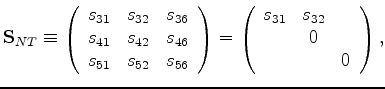

Expression of (41) can be made more compact by writing it as:

|

(42) |

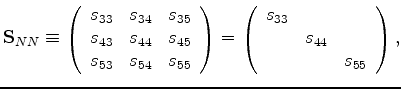

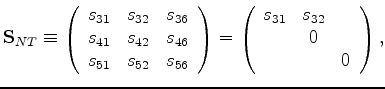

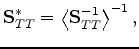

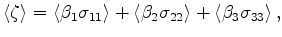

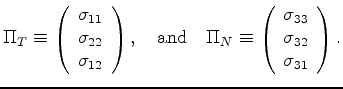

where

|

(43) |

|

(44) |

and

|

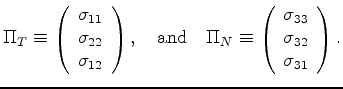

(45) |

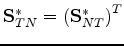

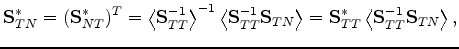

with

(with

(with  superscript indicating the matrix transpose).

Also I have

superscript indicating the matrix transpose).

Also I have

|

(46) |

and

|

(47) |

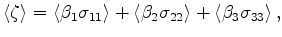

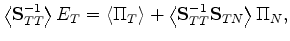

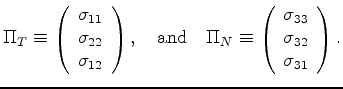

It is important to distinguish between ``slow'' and ``fast'' variables

in this analysis, since this distinction makes it clear when

and how averaging should be performed.

The ``slow'' variables, i.e., those that are continuous across the (here assumed horizontal)

boundaries and also essentially constant for the present quasi-static application, are

those contained in  and

and  . So, after averaging

. So, after averaging

along the layering direction, I have:

along the layering direction, I have:

|

(48) |

where

, and

all the starred quantities are the nontrivial

average compliances I seek. They are defined in terms

of layer-average quantities where the symbol

, and

all the starred quantities are the nontrivial

average compliances I seek. They are defined in terms

of layer-average quantities where the symbol

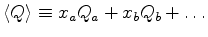

indicates a simple volume average of all the layers. By this notation I mean

that a quantity

indicates a simple volume average of all the layers. By this notation I mean

that a quantity  that takes on different values in different

layers has the layer average

that takes on different values in different

layers has the layer average

.

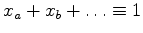

The definition is general and applies to an arbitrary number of

different layers where the fraction of the total volume occupied

by layer

.

The definition is general and applies to an arbitrary number of

different layers where the fraction of the total volume occupied

by layer  is

is  , etc. Total fractional volume is

, etc. Total fractional volume is

.

.

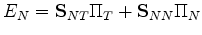

Of the three final results, the two easiest ones to compute are:

|

(49) |

|

(50) |

where

is the layer average of some quantity.

These results follow from this equation:

is the layer average of some quantity.

These results follow from this equation:

|

(51) |

which also followed immediately from the formula

|

(52) |

multiplying through first by the inverse of

, and then performing the

layer average. [Note that

, and then performing the

layer average. [Note that

and

and

are both

normally square and invertible matrices, whereas for most systems the

off-diagonal matrix

are both

normally square and invertible matrices, whereas for most systems the

off-diagonal matrix

is not invertible. But, this fact does not cause problems

in the analysis, because I do not need to invert

is not invertible. But, this fact does not cause problems

in the analysis, because I do not need to invert

in order to solve

the averaging problem at hand.]

These averages are meaningful because, when the matrix equations

presented are multiplied out, there never appear any cross products of two

quantities that are both unknown. [From this view point, Eq. (51)

is an equation for

in order to solve

the averaging problem at hand.]

These averages are meaningful because, when the matrix equations

presented are multiplied out, there never appear any cross products of two

quantities that are both unknown. [From this view point, Eq. (51)

is an equation for

, just as the unaveraged version of

(51) is an equation for

, just as the unaveraged version of

(51) is an equation for  in each layer.]

So simple layer-averaging suffices (thereby providing the main motivation and value

of this method).

Multiplying (51) through by

in each layer.]

So simple layer-averaging suffices (thereby providing the main motivation and value

of this method).

Multiplying (51) through by

then gives

the results (49) and (50).

then gives

the results (49) and (50).

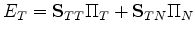

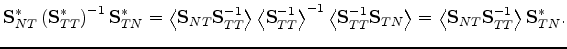

The remaining result is more tedious to compute, since it requires several intermediate steps

in its derivation. But the final result is given by the formula:

|

(53) |

To provide some clues to the derivation, again consider:

|

(54) |

which is just a rearrangement of (52). The point is that

is then given immediately in terms of the quantities

is then given immediately in terms of the quantities

and

and  , which are both ``slow'' variables and therefore

essentially constant. An intermediate result that helps to explain

the form of this relation (53) is:

, which are both ``slow'' variables and therefore

essentially constant. An intermediate result that helps to explain

the form of this relation (53) is:

|

(55) |

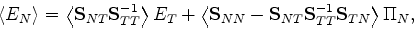

Substituting for  from (54) into

from (54) into

|

(56) |

and then averaging, I find that

|

(57) |

an expression that completely determines the remaining coefficients. After some more algebra,

the formula giving the final result is:

|

(58) |

Equation (58) contains all the information needed to produce

the third and final result found in (53).

Another check on these formulas is to compare them directly to those found

by Schoenberg and Muir (1989). However, direct comparison is not so easy,

since their analysis focuses on the stiffness version of these equations.

My treatment makes use of the compliance version instead. Since the symmetries

of the two forms of the equations nevertheless are nearly identical, cross-checks

and comparisons will be left to the interested reader.

|

|

|

| Mechanics of stratified anisotropic poroelastic media |  |

![[pdf]](icons/pdf.png) |

Next: APPENDIX B: POROELASTIC FORMULAS

Up: Berryman: Stratified poroelastic rocks

Previous: SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

2010-05-19

,

,![]() and stresses

and stresses

![]() that are necessarily continuous

across boundaries between layers, while the others are not necessarily continuous.

I have been implicitly (and now explicitly by calling this fact out) assuming

that the interfaces between layers are in welded contact,

which means practically that the in-plane strains are always continuous:

so if axis 3 (or

that are necessarily continuous

across boundaries between layers, while the others are not necessarily continuous.

I have been implicitly (and now explicitly by calling this fact out) assuming

that the interfaces between layers are in welded contact,

which means practically that the in-plane strains are always continuous:

so if axis 3 (or ![]() ) is the symmetry axis

(as is most often chosen for our layering problem), I have

) is the symmetry axis

(as is most often chosen for our layering problem), I have ![]() ,

,

![]() , and

, and ![]() are all continuous.

Similarly, in welded contact, I must have continuity of the all the

stresses involving the 3 (or

are all continuous.

Similarly, in welded contact, I must have continuity of the all the

stresses involving the 3 (or ![]() ) direction: so

) direction: so

![]() ,

,

![]() , and

, and

![]() must all be continuous.

must all be continuous.

,

,  (with

(with  and

and ![]() . So, after averaging

. So, after averaging

![]() along the layering direction, I have:

along the layering direction, I have:

, and

all the starred quantities are the nontrivial

average compliances I seek. They are defined in terms

of layer-average quantities where the symbol

, and

all the starred quantities are the nontrivial

average compliances I seek. They are defined in terms

of layer-average quantities where the symbol

and

and