|

|

|

|

Selecting the right hardware for Reverse Time Migration |

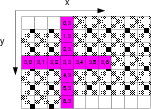

The core computation of RTM is finite-difference-based 3D

convolutions, which normally perform multiplications and additions on a number

of adjacent points. While the points are neighbors to each other in a 3D geometric

perspective, they are often stored relatively far apart in memory. For example,

in the 7-point 2D convolution performed on a 2D array shown in

Figure 7, data items  and

and ![]() are

neighbors in the

are

neighbors in the ![]() direction. However, suppose the array uses a row-major

storage and has a row size of 512, the storage locations of

direction. However, suppose the array uses a row-major

storage and has a row size of 512, the storage locations of  and

and ![]() will be 512 items (one line) away. For a 3D array of the size

will be 512 items (one line) away. For a 3D array of the size

![]() ,

the neighbors in the

,

the neighbors in the ![]() direction will be

direction will be ![]() items (one slice) away.

In software implementations, this memory storage pattern can incur a lot of

cache misses when the domain gets larger, and decreases the efficiency of the computation.

items (one slice) away.

In software implementations, this memory storage pattern can incur a lot of

cache misses when the domain gets larger, and decreases the efficiency of the computation.

|

|---|

|

convolution-2D

Figure 7. A streaming example of 2D convolution.[NR] |

|

|

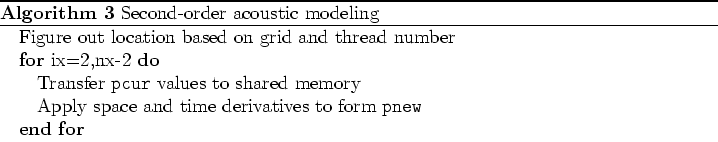

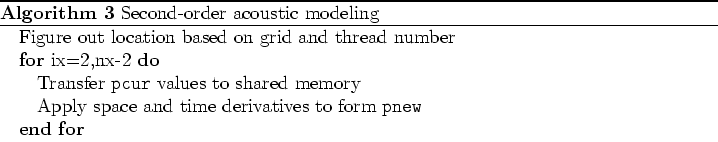

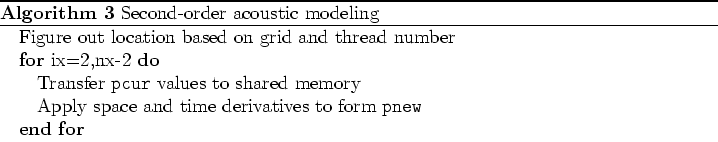

In an FPGA implementation, we use BRAMs to store a window of the input stream and enable

the circuit to compute one result per cycle. Figure 7

demonstrates this concept.

Suppose we are applying the stencil on the data item ![]() , meaning the circuit requires 13

different values (shown in red). As the data items are streamed in one by one, in order

to make the values from

, meaning the circuit requires 13

different values (shown in red). As the data items are streamed in one by one, in order

to make the values from  to

to ![]() available to the circuit, we use BRAMs to

buffer the window of all the six lines of input values from

available to the circuit, we use BRAMs to

buffer the window of all the six lines of input values from  to

to ![]() (shown

in grey grid). In the next cycle, the first value

(shown

in grey grid). In the next cycle, the first value  pops out of the window,

as

pops out of the window,

as  is no longer needed for the following computation. Meanwhile, the next

value

is no longer needed for the following computation. Meanwhile, the next

value ![]() is pushed into the window buffer, as

is pushed into the window buffer, as ![]() is needed for the next

stencil operation.

is needed for the next

stencil operation.

Considering the BRAMs as the `cache' of an FPGA design, the above window

buffer mechanism provides a perfect `cache' behavior: firstly, the data item gets

streamed into the window buffer at exactly the cycle that the data item is needed

for the computation for the first time; secondly, the data item only resides in the

window buffer for the period of time that the data item is needed for the computation.

Current BRAMs can hold 6MB of data, or 1.5 million elements, when the data is stored as float.

The window size that needs to be buffered is proportional to ![]() , where

, where ![]() is the spatial derivative approximation. For large data volumes and high

order stencils, this exceeds current BRAM storage, requiring domain decomposition. The

size of BRAM tends to follow Moore's Law, doubling every 18 months.

is the spatial derivative approximation. For large data volumes and high

order stencils, this exceeds current BRAM storage, requiring domain decomposition. The

size of BRAM tends to follow Moore's Law, doubling every 18 months.

|

|

|

|

Selecting the right hardware for Reverse Time Migration |