|

|

|

|

Selecting the right hardware for Reverse Time Migration |

.

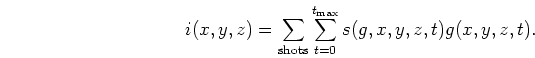

The explicit time marching scheme described above has an operation count proportional

to the number time steps

.

The explicit time marching scheme described above has an operation count proportional

to the number time steps An unmentioned aspect of the time marching scheme is that our physical experiment takes place in a half-space while our computational experiment happens in a more limited domain. As a result the computational experiment has artificial reflections from the boundaries of the domain. The reduction of these effects is usually handled through one or more of the following techniques: introducing a damping region around the computation domain (Cerjan et al., 1985); introducing a boundary condition that attempts to kill energy propagating at some limited range of angles perpendicular to the boundary (Clayton and Engquist, 1980); or, most effective, costly, and complex, using Perfectly Matched Boundary (PML) (Berenger, 1996) which simulates propagating a complex wave whose energy decays as it approaches the boundary.

A third problem is that it is impractical to store the 4-D volumes ![]() and

and ![]() in memory. These volumes are often multiple terabytes in size. As a result, for

a second-order time approximation,

we normally keep in memory only the previous two time steps needed to

update the wavefield. This

causes a problem with our imaging condition where

the source field must

propagated from

in memory. These volumes are often multiple terabytes in size. As a result, for

a second-order time approximation,

we normally keep in memory only the previous two time steps needed to

update the wavefield. This

causes a problem with our imaging condition where

the source field must

propagated from ![]() . to

. to

![]() while the receiver wavefield must

be propagated from

while the receiver wavefield must

be propagated from

![]() to

to ![]() yet the fields must

be correlated at equivalent time positions. To solve this problem,

one propagation must be stored either completely or in a check-pointed

manner to disk.

Symes (2007) and Dussaud et al. (2008) discuss checkpointing methods to handle the different

propagation directions.

yet the fields must

be correlated at equivalent time positions. To solve this problem,

one propagation must be stored either completely or in a check-pointed

manner to disk.

Symes (2007) and Dussaud et al. (2008) discuss checkpointing methods to handle the different

propagation directions.

A fourth potential problem is the very large size of the image domain required when constructing subsurface offset gathers. This is a particular problem for some accelerators with limited memory.

|

|

|

|

Selecting the right hardware for Reverse Time Migration |