|

|

|

|

Integral operator quality from low order interpolation or Sometimes nearest neighbor beats linear interpolation |

![\fbox{\includegraphics[width=0.68\textwidth, clip=true, trim=0pt 0pt 0pt 6pt]{/wrk/sep147/stew1/Fig/3DPSTMCME211.pdf}}](img5.png)

``Normally, an interpolator is selected based on its guaranteed-to-be-no-worse-than fidelity. However in the present case the distribution of many thousands or even millions of fractions of a sample to interpolate is uniform and so I focused in on the average rather than the worst case. From this perspective, looking at the amplitude behavior halfway between the 3rd and 4th curves plotted in the slide, the quite inexpensive linear interpolation does a good enough job in retaining fidelity. A similar plot of phase accuracy yields the same conclusion.''

To understand this concept, let us take the very simple case of a single function replicated with linear delay and sampled with unit spacing as illustrated in Figure 1. Applying linear moveout and stacking would ideally reproduce that function. In order to apply the linear moveout we need to interpolate. Let us first consider what happens if we use simple nearest neighbor interpolation.

|

simpledip

Figure 1. Simple dipping synthetic section. |

|

|---|---|

|

|

We generally abhor nearest neighbor interpolation because it (a) is a discontinuous function of position and (b) can yield interpolated values that don't even have the correct sign. When stacking is included, though, to a good approximation we may assume the interpolation points are randomly distributed between samples following a uniform distribution. This means that the output values on our stack at are approximately

|

by a boxcar having Fourier transform

by a boxcar having Fourier transform

to

to  , the spectrum

(1) is positive,

indeed greater than or equal

to

, the spectrum

(1) is positive,

indeed greater than or equal

to  . Therefore

we can compensate for the nonflat spectrum by simple zero-phase spectral

rebalancing after the stack, avoiding the expense of costly high quality

sinc-like convolutions before stack.

. Therefore

we can compensate for the nonflat spectrum by simple zero-phase spectral

rebalancing after the stack, avoiding the expense of costly high quality

sinc-like convolutions before stack.

|

|---|

|

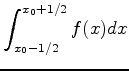

nnint

Figure 2. Nearest neighbor boxcar filter (left) and its spectrum (right). Figure from Fomel (2000). |

|

|

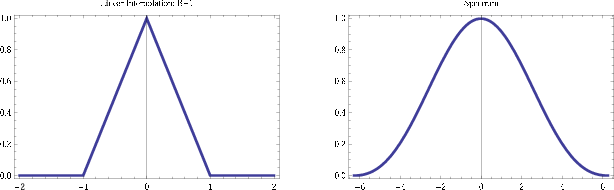

Seeing that nearest neighbor interpolation works unexpectedly well,

let us turn our attention to linear interpolation. Following the

same line of reasoning leads to a triangular convolution illustrated

in Figure 3 which is a convolution of the nearest

neighbor boxcar with itself and hence a spectrum that is the square

of (1). This linear interpolation result is poorer than

nearest neighbor, requiring more post-stack spectral compensation

and concomitant noise magnification at higher frequencies!

|

|---|

|

linint

Figure 3. Nearest neighbor boxcar filter (left) and its spectrum (right). Figure from Fomel (2000). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Integral operator quality from low order interpolation or Sometimes nearest neighbor beats linear interpolation |