Jos Claerbout : First letter from Alaska

Jos Claerbout : First letter from Alaska

photos added by Popster

5/23/94

We arrived in Anchorage around two in the

afternoon on Friday. Our initial excitement and

plans to "just pitch our tent outside the airport",

were dampened somewhat by the information

woman's insistence that Alaska isn't "just one big

wilderness area." As we sat in the airport the theme

that would soon repeat itself sunk into our heads,

"we have no plan, we have no plan." Would

misery exist without expectations? It was soon

ascertained that money would have to be spent

(and after our pre-departure splurge, this wasn't

appealing to either of us) and the local youth

hostel came up as the winner. In economics, the

concept of an externality is defined as something

that arises out of an activity that affects a third

party in a way not necessarily intended. They

can be positive (you like listening to the local

school band practice) or negative (like

pollution). Youth hostels are an excellent

example of something that can yield positive

externalities. Put a bunch of travelers together

in a very small place and guess what? They

exchange information. It was quickly

discovered that our initial destination, Homer,

was full of people like ourselves (clueless,

unemployed) and that Seward was really our best

bet.

5/23/94

We arrived in Anchorage around two in the

afternoon on Friday. Our initial excitement and

plans to "just pitch our tent outside the airport",

were dampened somewhat by the information

woman's insistence that Alaska isn't "just one big

wilderness area." As we sat in the airport the theme

that would soon repeat itself sunk into our heads,

"we have no plan, we have no plan." Would

misery exist without expectations? It was soon

ascertained that money would have to be spent

(and after our pre-departure splurge, this wasn't

appealing to either of us) and the local youth

hostel came up as the winner. In economics, the

concept of an externality is defined as something

that arises out of an activity that affects a third

party in a way not necessarily intended. They

can be positive (you like listening to the local

school band practice) or negative (like

pollution). Youth hostels are an excellent

example of something that can yield positive

externalities. Put a bunch of travelers together

in a very small place and guess what? They

exchange information. It was quickly

discovered that our initial destination, Homer,

was full of people like ourselves (clueless,

unemployed) and that Seward was really our best

bet.

Land of the falling rain

After a few too many hours in a bus station, 2:30

Saturday afternoon found us on a bus to our

aforementioned destination. I spent most of the

three hour trip admiring the scenery and

reading the second paper that I had picked up in

Anchorage. The town came off as pretty

civilized for a place that was said to only have

2,000 people, tops.

We stepped off the bus a little before six straight

into a good downpour in 35 degree weather. This

was unquestionably John's and my trial by

water. We had come prepared for the worst --- 2

large tarps, 2 tents, 2 thermorests, plenty of

stakes --- preparation that was not in vain. As

we stumbled sumo-wrestle toward our campsite

under the weight of our glad bag wrapped

backpacks, I began to question my "dry

sandwich" approach to camping in the rain. The

theory was one tarp underneath the tents side by

side, and one tarp above, either suspended in the

trees or weighted or tied down. A nice theory,

but in practice its dry implementation would

prove considerably more difficult.

Our campsite was shared by four other tents all

of which would be gone by morning. Had we

known what was in store, we might have done

the same. So there we were, standing utterly

rain proof, wondering how our current situation

would translate into a like one inside of our

tents.

Our campsite was shared by four other tents all

of which would be gone by morning. Had we

known what was in store, we might have done

the same. So there we were, standing utterly

rain proof, wondering how our current situation

would translate into a like one inside of our

tents.

We first dropped the ground cover, the bags on

tops of it, and finally, the rain tarp. While

cumbersome, the operation kept each one of us

dry while setting up our sleeping

accommodations underneath. Our first attempt,

which secured the tarps with nothing more than

shallow stakes in the rocky earth, failed

miserably and when the wind started nearly

whipping us into the air, our tent security was

replaced with rocks and cords through the tarp's

grommets.

Despondency, disillusionment, and an offer

I'm wording this entry on the tenth of June and

am now obliged to recap the past three weeks.

The rain that greeted us did not let up for four

days. (It had been going for a week before that.)

Morning pulled the curtain of exhaustion far

enough away to allow me to appreciate the

beauty of my surroundings. We were camped on

the rocky shore of Resurrection Bay, a deep inlet

into the Kenai peninsula, upon which one of

Alaska's first towns was founded. 4,000 foot

mountains surround the bay and the strip of

land that separates them from the sea. If last

night's stay in the hostel had allowed any doubt,

it was now clear that we were in Alaska. And

even clearer that we were unemployed. And

thus was born the twice daily "walk to the docks",

a one mile beachside trek that landed us on the

wooded planks of potential employers. While we

were camped near a downtown spending center

in this town of 3,000, the earning center was a

bit of a walk.

Our first trips gave us nothing more than an

understanding of the workings of the harbor. It

docked mostly work ships in the north and

sailboats and charters toward the south. It also

fostered an interesting multicultural atmosphere

(although not by the color-conscious ethos of

those who define themselves as "ists" of the

latter) by docking many boats owned and

operated by ethnic Russians (who, I later found

out, lived in Alaska without losing their

geographic and social identity). I had the

pleasure of speaking with one of the captains

whose full sized beard came down to his mid sized

waist riding pint sized legs. Nationally Chinese, I

found he was Mongolian, but unfortunately

spent more time speaking with his young peer,

an 18 year old thrown out of high school for

"sexual harassment" who seemed unrepentant in

his egoism. Alaska certainly isn't worried about

drying up its supply of odd characters. It is they

who I am determined will pepper these pages.

Our second day of dock walking resulted in the

chance meeting with Perry Buchannan, long

time owner of the seiner/longliner Dolly B. (I'll

try to explain the fishing terms later on.) He

said he would probably need workers for the

halibut opener, a 24 hour fishing extravaganza

on June 6th. As this was just the 23rd of May and

he didn't want to talk to us again until June 3rd,

we were left with free time and uncertainty

were we to take the offer as solid or as just a

possibility. What was the best way to, as Jack

would put it, look out for number one without

stepping on number two? We decided the best

way was to stay in the dock area and familiarize

ourselves with these novel surroundings while

seeking any work to tide us over and stem the

flow of money out of our wallets.

We learned it was day two of the ten day black

cod season (look for an econ. rant later on)

which we were too late for. After that came

halibut and our best bet for employment seemed

to be processing jobs at the local canneries until

the third rolled about. The very friendly

employment service in town tipped us on to two

local canneries that might or might not be

hiring. Icicle Seafoods and Dragnet Fisheries. (I

hear the latter always gets their fish.) We were

off.

Upon our arrival at the behemoth Icicle, we

were directed toward the personnel department,

Anne Green. The directions were given to us

very slowly, with lots of hand signals and

positive reinforcement. I guess the connection

between uncleanness and stupidity is close in

many people's minds. After winding our way

through an enchanted forklift and conveyor

belt jungle, Annies office appeared. She happily

accepted our applications --- happy, because she

didn't need to hire us now, but reserved the

option for a few days hence. Off to Dragnet.

Next to a large orange dock, this Fish

Detective/processing agency was just the

opposite of Icicle. Where Icicle was a towering

gray warehouse, Dragnet was 4 portable trailers

with squatters under the dock. Jack was the man

I was to talk to. Approaching the door I was

greeted by another figure leaving the center

portable with heavy facial hair and an enormous

gut. I suspected I had found my man. Positively

identifying himself, Jack, in his brusque and

fluid manner informed us of everything that

Anne had, telling us to check back the next day.

We did, and upon doing so were jokingly

lambasted by Jack for squandering a day as

beautiful it could only be spent "chasing pussy

and drinking beer." He went on to talk to us and

another one of his workers for several minutes.

His type was one with which I was not well

acquainted. Words and sentences flowed from a

growling throat that demanded credibility. He

was lamenting the loss of two of his workers to

Anderson's, another processor. "Sure, they'll get

work now, but they'll get screwed come the 15th.

There's no loyalty at a place like that. You come

work for me and you've got a job through

September. Here for ?? more weeks, then to

Dillingham, Kasilof, Dutch Harbor, Bristol Bay..

The worker, who reminded me amazingly of an

oversized (?) Piggy from Lord of the Flies

bubbled out his adoration of an agreement with

his boss (minutes before, in a private

conversation with John and I, he wondered why

he wasn't going to Anderson's as well. Nothing

was coming into Dragnet.)

Jack's manner was one of supreme self reliance.

To question anything, he said was to place yourself

in battle against a rabbit in a briar patch. While

I may have privately questioned some of what he

said, none of my incredulity slipped into my

speech. I know where I'm outclassed. Jack's

personality was magnetic and I was drawn in. I

quickly decided that "The true Alaska experience

could be quicker found under the docks of

Dragnet than in between the corporate walls of

Icicle. I would prove myself much more right

that I would have preferred.

By the close of the first week in Alaska, John and

I moved in under the Dragnet dock. The cod

season was to finish noon the following day and

many boats were to be expected. So 2 PM Friday

we packed up our stuff and made the 1-1/2 mile

trek to our future employer. No boats had

arrived so we prepared more food. We had been

carbo-loading for the past 24 hours fearing the

48 hours on, 12 off, 48 hours on work schedule

that Jack had described was endured by last

year's crew. At 6 dollars an hour and overtime

after the first 8, ALASKAN BIG MONEY was

finally headed our way, right?

The anxious crew of 10 saw an uneventful day of

stone pitching turn to an evening of the same.

Saturday rolled around and the dearth of boats

spun the wheels of the rumor mill as all of us

tried desperately to figure out why all boats

entering the bay veered right, toward Icicle.

When the entire day yielded only one 14,000

pound catch (about 3 hours for a 6 man crew) I

became curious myself and more ready to believe

that Jack had somehow done something to "piss

off" the fishermen. If this were true, we were

all in trouble. My conversations with Norma in

the office yielded the shielded admission that

"someone might have said something" to anger

the fishermen, who had decided to show Dragnet

just what a bad idea it was to piss them off.

Only two ships came in Sunday. The total three

were all registered in Seattle and a ten year

patron of Dragnet decided to go elsewhere, all of

which lends support to the theory above. And so,

without working an hour, came to an end of my

time with black cod in Alaska.

It marks my first experience as a member of the

exploited proletariat. I couldn't complain too

much though, 4 crew members had been shipped

from Kenai (120 miles away) with big

expectations. My travel had been limited and

rent there cost me $6 less a night (that is, zero)

than at the campground. I also got to see

another marvelous economic principle in action.

Stacked on the dock were hundreds of pallets,

those 2x4 contraptions used to stack goods on. We

put some under our tents and burned around 2 a

day for food and warmth. Our private cost of

retrieving the pallets was only about 5 minutes

each. Dragnet, however, probably lost a few

dollars for each one we burnt. Any feelings of

guilt were quickly absolved upon the realization

of my relative abject poverty.

John and I had been disappointed with our

experiences in Alaska up till now (he more than

I, years of travel have taught me the value of

diminished expectations). We hoped that

another trip to the Dolly B would straighten

things out. It did, sort of.

Long lining and other ways to lose your hide

A few harried trips between town and the docks

finally secured us what we were looking for --

fishing jobs for halibut. After talking to many

people I learned that the average share (given to

a deckhand) of a halibut catch was somewhere

between $20 and $2,000. It was known to be a

gamble. But when Perry let us move into his

boat a few days before the opener, that gamble

became a sure thing. As romantic

(retrospectively) as dock life may be, a kitchen

is a wonderful thing. Now, I'm going to skip a lot

here, just so I can get to the description of long

lining. If this takes any less than 15 pages, I'll

be surprised.

Cuttin'

This is the first stage John and I were involved

in. (Oh, before I go further --- I'm going to

describe all this in excruciating detail --- I'm

sorry in advance if anyone gets bored. But

knowing my readership, fish stories are always

welcome.) Herring was the bait to be used.

Packaged in boxes of 110 we were to cet the

thawed fish in half and dump them into our

individual bucket. Each layer of fish had to be

salted generously to avoid spoiling. Between the

three of us we cut about 16 boxes worth. Bear in

mind that there were 3500 hooks that awaited

bait, a fact I put as far out of my mind as possible.

I applied to variants of the same work ethic to

my labors.

The first was one I had learned with

the CDF

[California Department of Forestry and Fire Prevention]

on a dangerous day assisting tree

removal near power lines. There are times to

joke and there are times not to joke. When one is

in danger of losing a thumb, it is not a time to

joke. It is as my father had commented about his

uncle Fritz, an otherwise very personable fellow

-- you just couldn't talk to him when he was

operating a power saw, he wouldn't say

anything. Am I finally learning discipline?

Nevertheless, the job was done and the salted and

covered tubs were put away for the night.

The first was one I had learned with

the CDF

[California Department of Forestry and Fire Prevention]

on a dangerous day assisting tree

removal near power lines. There are times to

joke and there are times not to joke. When one is

in danger of losing a thumb, it is not a time to

joke. It is as my father had commented about his

uncle Fritz, an otherwise very personable fellow

-- you just couldn't talk to him when he was

operating a power saw, he wouldn't say

anything. Am I finally learning discipline?

Nevertheless, the job was done and the salted and

covered tubs were put away for the night.

Baitin'

This was done the morning of the fifth. It was

now time for those freshly sharpened hooks to

pierce tender fish flesh -- and by my arduous

accomplishment. The hook was an ugly affair.

(I've kept one and picture it at right). About 3

inches long and 2-1/2 inches wide. Each

herring piece was to find a home double pierced

on these hooks. My speed was good -- over 500

an hour -- a rate which qualified me for the

dubious title of "Masterbaiter", a pun of such

caliber that I had not heard it since I left Hawaii.

My fingers still have holes in them from this

exercise. Not as many holes in them as the fish,

though. Upon completion of three hours work,

we were done. Each baited hook (with attached

ganyon and becket) was laid in a tub, circularly

filling it incrementally. The ganyon was an 18

inch cord that ran between the hook and the

becket, the large snap at the end. A becket looks

something like this. By placing one's hand

around it with the thumb here, it would snap

open, and could be effectively attached to the

drag line. I have managed to acquire one of the

marvelous contraptions for the belated benefit

of all interested parties.

Fun

So, the afternoon of the fifth, we were off. It

took us 3-1/2 hours to reach Cliff Bay, where we

anchored for the night. Like so much of coastal

Alaska it was impossibly and effortlessly

beautiful. Thickly wooded slopes of mountains

veered toward the water, stopping just inches

short of dropping their growths into the flat jade

pool that lapped at their precipice.

Unfortunately, more earthly (or rather,

humanly) responsibilities beckoned to John and

I inside. We were to cook dinner -- chili cheese

burgers. Let me assure you, I was thrilled. But I

have to do this stove justice. Let me try, as fairly

as possible, to recount Perry's instructions for its

proper lighting.

Alright, first open up this wing nut -- that lets

the diesel down there to the burner. If you take

off this metal lid, you can see the diesel flowing

into the chamber there. Now, get a paper towel

and SET IT ON FIRE, then THROW IT DOWN THERE.

Replace the lid (emphasis added). After Perry's

initial explanation, John and I were able to

repeat only one phrase to each other for the

next hour. "Take a lit paper towel and throw it in

the gas." Ah, adventure.

Well after several meals we both had 4 eyebrows

between us, which was a good sign, and felt

adventurous enough to attack an actual meal (on

my list, chili cheese burgers served on toast

ranks pretty down low for actual meal, but in

Perry's $135 foray into the supermarket for pre-

departure food, it was one of the only things that

had emerged. We did, however, have enough

Mountain Dew and Cheetos to last us a lifetime.

And eating like this, that wouldn't be long.

Well, I'll save you the bore of the entire cooking

saga, which I think is better reduced to a few

sample quotations.

"Wow, that's a lot of grease."

"If I were you, boys, I'd use a skillet."

"Ya know, I bet if we slid this knob to open,

there'd be a lot less smoke in here."

"Are burgers supposed to look like that?"

And the meal, once served, can best be described

by just two words.

"Mmm. Diesel."

Sleep came

early as tomorrow we had to be up for the 5 hour

trip to lay our first line. (I'll explain all that in a

bit.)

I woke up to the singular churn of a boat motor

laying steady noise after the intermittent burst

of a wave clap under the hull (not

coincidentally, where I slept). I lay in bed,

awake, for at least an hour, and although not

seasick, could not help but remember my vain

attempts at age 6 to convince my mother I was

suffering from a heart attack while crossing the

English channel by car ferry. (Anyone not

understanding this reference, should consider

themselves better off for it.) I was more

comfortable laying on the floor then, and things

seemed not to change much in more than a

decade. Upon finally getting up, I found I was a

lot better off outside, which is where I decided to

situate myself. The ride was uneventful and at 12

PM we were ready to start laying gear.

And now, a digression

A short story of kinesthetic stupidity two years

ago during my tenure at CDF

[California Department of Forestry].

Bill (a fellow in his

late 40s) and I were assigned the complicated

task of throwing logs from one truck to another.

These logging trucks were each about nine feet

high and spaced two feet apart. Each log chunk

weighed about 35 pounds and was to be thrown

from the bed of the full truck (which we stood

in) to the bed of the empty one (2 feet away).

This went on quite fine until I picked up a rather

large log with the intention of doing to it what I

had done to its brethren. About midswing I

decided I didn't have quite enough momentum so

chose to hold on to the log rather than release it.

This was fine with my wooded friend who had no

qualms with taking uninvited company to see his

peers which is just where I went. My leg

collided with enough force on the side of the bed

as to cause a paint stain of my clothed shin. My

body, thankfully, was luckier and landed in the

gently mocking confines of a bed of wood. And

so was born Jos the flying squirrel.

Clippin'

This is probably the most dangerous aspect of

long lining and also, not surprisingly, the stage

where Perry and Dan (the other crew member)

had decided we had matured enough to get by

without a significant amount of their help. Now,

to long line, you put out skates (sometimes a

skate is quixotically defined as 10 skates strung

together). Each lesser skate is about 1800 feet

(the most you can get in a box). Therefore, each

greater skate is 3-1/2 miles, of which our boat

has 3. These were all wound onto an enormous

spool mounted on the stern of the Dolly B, about

three feet from the edge. Now, to put out a skate,

it was first necessary to put out a big floating

flag and a buoy, which marked the beginning of

the line. To these, more than 100 feet of rope (I

forget just how much) are attached, the end of

which hooks on to the anchor, which is in turn

connected to the first skate. Obviously, the

beckets must be attached to the line as it goes out.

This is where John and I came in. We were to

kneel on the stern, facing the sea, in between

the spool and the end of the ship. We each had a

tub of 250 pieces of bait with ganyons attached

by our side. Now, when the first skate started

lowering into the water, the stress began. The

line passed over my right shoulder and the bait

was by my left. It was the opposite for John.

And since the rope was spooled, it would swing

from one side of the boat to the other as it

unfurled. Dan was quite proud of showing us all

the holes it had burned in his jacket over the

years. I was determined not to have any such

points of pride myself. So here's the routine.

Rope starts going out. I reach into my tub, grab

a becket and snap it on. 15 feet later, John does

the same. Repeat. Easy, right? No. Let me just

list enough complications to make mother wince.

The first one is speed. From the time a becket is

snapped to the line, I had about seven seconds

before I had to snap the next one. Bear in mind

that there's 250 ganyons in one of these tubs and

the hooks get messed up pretty frequently.

There was no time to stop the line, so if one of us

got stuck, the other would have to do double time.

The second is that a becket is not the easiest of

snaps and attaching it to a line whizzing by at 3

miles an hour ain't so easy either. I dropped

four ganyons total during this phase, John

three. The rope had to be stabilized prior to

snapping, which is why we wore gloves.

Unfortunately I had my cloth glove on my right

hand and my leather one on the other. By the

time I realized it, I had already burned a cute

little hole in the crotch of my right hand. Still a

gross little thing a week later. Even with the

leather glove I managed to give myself rope

burn on my middle finger.

Now, besides all this, snapping is dangerous for

the kinesthetically stupid, which is why I

mentioned that CDF story a while back. I tend to

be kinesthetically stupid, a defect I balanced by

taking this job incredibly seriously as well as

taking as many precautions as I could.

What makes it dangerous is the possibility of

getting hooked and taken off the boat. Once that

becket is snapped, that line is going out, with a

dangling hook attached. And before you think

I'm joking, bear in mind that this gear is

designed to catch fish that weigh over 300

pounds, compared to my paltry 180.

There are, of course, ways to avoid this. The best

is the one I followed, and did for 3-1/2 hours

while on my knees:

- Grab bait in tub with left hand, becket with

right.

-

Switch hands, throw bait overboard (while

holding on to becket).

-

Snap becket on.

It worked, I'm alive, but your knees really start

to get to you after a while. Course, after laying

three of these, there was yet more work to be

done. And not just more work, but REAL work.

Pickin'

Now here's where things get interesting. By the

time we had laid the last skate, it was time to pick

up the first. We did this by bringing it up the

side through some rollers, and back to the spool.

Dan, who was experienced, would pick the

beckets off the line and throw them onto the

"table". (I have no better way to describe the

rectangular cover for the hold. It was about

three feet high.) Once on the table, it was John

and my turn. For the first skate, he took the job

of hook replacer and I of hook remover. Most of

the hooks came up with nothing, and when

thrown on the deck, John would coil them

around the lip of one of our friendly tubs. Now

when a fish other than a halibut was attached, I

had to take out the hook from the mouth (or the

head, or the eyeball) of this "junk" fish. At first,

I proceeded with great difficulty. My experience

in this realm was somewhat limited and the cod,

shark, flounder, and skate that had the

misfortune of coming my way often died before I

could return them to the water. It should be

noted that birds have a fascinating reaction to

large dead fish. They know that it's food, but they

just don't know how to eat it. Nothings funnier

than a swarm of ducks surrounding a belly up

cod, all of them fighting for property rights, but

having not the foggiest notion of how to eat the

damn thing.

Well, I was continuing to blunder along when

one of these two foot sharks came close to

chomping down on my finger. (They didn't have

much in the way of teeth, but one hell of a bite,

let me assure you.) That's when the idea of

forcing my fingers downs these fish's throats

lost its favor, and ramming the becket down

there to keep the mouth open came into fashion.

And if you can picture me stooped over a fish,

hands going furiously, instruments in its mouth,

you see that there was only one possible title I

could be given -- Jos Claerbout -- Fish Dentist!

This realization bred a whole sick sort of office

chatter I would engage in with my patients. "Oh,

yeah. I see your problem now. It's this hook that

goes in your mouth and comes out your eyeball."

"Now, you're going to experience some

discomfort." "Hey, that's weird, you've got the

same problem as the last guy."

At times my tone was compassionate and

conciliatory. "You want the hook out, I want the

hook out." But at times I admit I lost my temper:

"Stop bleeding!"

All in all, though mortality rates dropped to

about 25% with my more personalized service.

And one last note on junk fish -- skates. They're

the ugliest damn fish I've seen in my life. Here,

I'll try to draw the underside of one for you.

All in all, though mortality rates dropped to

about 25% with my more personalized service.

And one last note on junk fish -- skates. They're

the ugliest damn fish I've seen in my life. Here,

I'll try to draw the underside of one for you.

Well not very good, but suffer.

So, on the off chance we actually caught a

halibut (commercial fishing seems to be the

moral equivalent of cutting off your head to

eradicate pimples) it would be pulled out of the

water with either a) hand on the ganyon, b) a

large, fireplace poker-esque object, c) tongs, d)

all three, which invariably caused all of us to

cuss out the others as incompetents and

weaklings. We were swearing like ... never

mind. So every couple hundred hooks, we'd pull

up a halibut, and once it had been measured

(they had to be over 32 inches) it would be

attached to a line strung along the port side of

the ship (we were picking off starboard). Had

we had a large catch (over 10,000 lbs), we would

have had to stuff the fish in the hold. Normally,

a crew of four allows you to clean them right

after they're picked, but as neither John nor I

knew how, this would have to wait.

We started picking the first skate around 6 PM.

It was dismal. We pulled in fewer than 20 fish on

the whole thing. But because halibuts are big

fish (anywhere from 25 to 350 pounds) it wasn't

a total skunk. The second skate was better, but

comparatively pathetic to the 15,000+ pounds

that Perry had been hoping for. Highlights

included a ten foot shark that has managed to get

hooked in the head (the ganyon was cut when

we saw it) and some 70 pound halibut. It was

almost surreal, working until 3 in the morning

with the wind gushing, the boat rocking, our

bodies racked with cold and fatigue (okay, I'm

exaggerating) plunging on. We were twenty

miles off shore and the only bright light came

from the lamps mounted on the ship itself. We

worked as an effective team, no complaining

until the job was done at 3:15 and we were in bed.

6:15 same day. I awake, Perry tells me it's time to

get started. As I grumble in the kitchen trying

to decide what to eat for breakfast, Dan asks me if

I'm ready to start yet. Reeses peanut butter cups

and 4 Ritz crackers won the day. Breakfast of

champions.

We started picking the third skate almost

immediately. Perry had been up for an hour

navigating us to the site. As I took the job of

hook replacer it quickly became evident that we

were picking our way towards an Alaskan skunk

in the box. I collapsed into my bed at 11:30

uncertain of my share, uncertain of the price of

halibut, but certain of one thing -- we did not

have much.

My sleep was jarred by the fear that our

fiberglass hull would not live to tell its friends

about the spankings it was delivering to the

waves. And at 5 PM, June 7th, I was woken up

with the phrase, "Come on, time to clean some fish".

Jos Claerbout gonad extractor/goop scooper

Before I start this, I should mention that its

been almost two weeks since I've written. More

on Day of Despondency later.

So, coming into the harbor we had to clean the

(now thankfully) small number of fish we

brought in. Since neither John nor I was

experienced, this was accomplished assembly-

line style. Dan took the head, effectively (and in

scarcely more than one motion) cutting out the

gill plates, and getting, as a special bonus, the

entire set of internal organs! It was then passed

onto me, where I would reach into the body

cavity, wiggle my fingers a bit, and retrieve a

homendashen shaped thing. Yesiree. Fish

gonads. And don't I feel inferior now. Holding a

testicle the size of your hand is a most .. singular

experience.

I would then spoon out the bloodline and some

interesting goop at the top of the spine

called the

'sweet meat.' I won't even venture to guess

what this was, as I suspect fish don't have

sinuses. This whole process took a little over an

hour, as we had fewer than 100 fish. John would

clean the fish off and drop them into the hold.

Stuff! stuff, dammit!

As we drew nearer and nearer to dock (to sell the

fish), it became increasing necessary to provide

the illusion that these fish had been chilling in

the hold on one ton of ice instead of working on

their tummy tans for the past 24 hours. This

necessitated stuffing the fish with ice, a process

that even without time constraints was difficult

as our hands quickly froze underneath our

gloves. Two minutes after finishing this it was

time to remove the hold cover as we had docked

and now we were to unload the fish.

A net dropped into the hold and we threw them

in. There's really not more to it than that and

I'm three weeks behind on the journal.

So ... cutting to the chase, the 2,074 pounds of

halibut, at 1.35 a pound, at a 8% share, minus gas

and food (loved those Cheetos) I get a check for

$164 dollars. Boy, that's almost five dollars an

hour!

Aftermath-fallout

Well, it was a letdown. But it turns out Perry was

going to seine for salmon at the end of the

month, so we had jobs with him. Well, not

exactly. He found somebody who was

experienced, so we were effectively un-hired.

Then his son, Steve, hired both of us, later

saying there was only room for one of us. As the

handwriting on the wall couldn't get much

larger, I decided to hit the road.

Jos, on the road

So, 7:30 PM on a Thursday (the 9th, I believe) I

decide to go to Kenai,

then maybe to Homer.

The bus?

No way, man,

I'm becoming an advanced wanderer.

It was time to start hitching.

So I head out of town, totally overburdened with

gear, until I come across a road sign reading:

Moose Pass 22

Anchorage 95

Homer 120

I'm not sure on those distances, but it's not off

by any factor greater than two. Like my

approach to so many endeavors, I decide to bring

some levity to this seemingly despondent art and

become the Happy Hitcher.

I would accomplish an effective rudimentary

hand relationship with drivers as follows:

Car approaches. Jos holds up hands in front of

him with grin on his face. Meaning --- 'Okay,

check out this great idea!' Next he points at car.

Meaning --- 'You'. Then by painting to Moose

Pass on the sign, an extremely reasonable

destination. Then a thumbs up meaning --- Jos

thinks it would be a good idea for you to take him

to Moose Pass. Always wanting to hear the other

side, I would then turn to the driver and shrug

with my hands out, soliciting their opinion. This

was usually accomplished by them driving past,

an act I saw as a bit rude considering my

extensive roadside theater. I kept in good spirits

(I figured people are more likely to pick up a

smiling hitchhiker) by verbalizing my hand

motions. It was hard not to laugh hearing

myself repeat 'You, me, Moose Pass, good, okay?'

over and over.

While most drivers just drove on past, several

pointed to their left. I had a bad feeling they

were saying 'Hey, idiot, if you want to go to

Moose Pass, why aren't you on the right road?

Moose Pass is over there!' It was only later that I

learned they were in fact attempting to

communicate 'No, you idiot, why are you trying

to hitch from me, I live here.'

So then the first hitched ride of my life came

along. A 35 year old driving a jeep Family wagon

with a child seat in back, I felt secure. And so I

met Leif.

Norwegian by blood, Leif looked every bit his

thick blond heir and a mustache to match, he

was only about 50 pounds short of being Thor.

He was very personable and I quickly learned

that the bullshitting skills I have worked so hard

to acquire over the course of my life made me

the perfect hitcher. We discussed all sorts of

things, (including boats) but what I found

interesting was when our talk would turn to his

impending marriage. He was a laconic as they

come, but when we got to this topic, he actually

choked up. It was like nothing I had ever seen.

It was still a year off and made him as jittery just

thinking about it. Date lots of people. A mantra

oft repeated by mother and one worth following

to avoid the crisis of self doubt this fellow was

facing. And a bit after the town of Moose Falls,

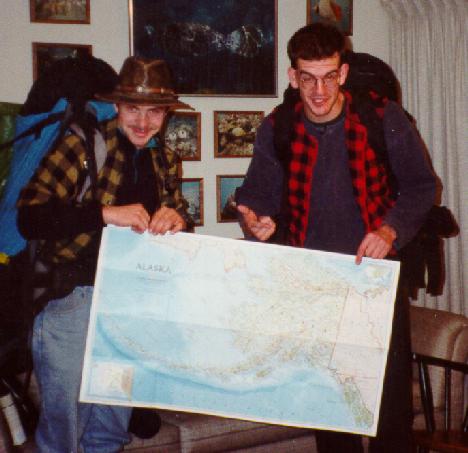

he drops me off, at the fork in the road. (Okay,

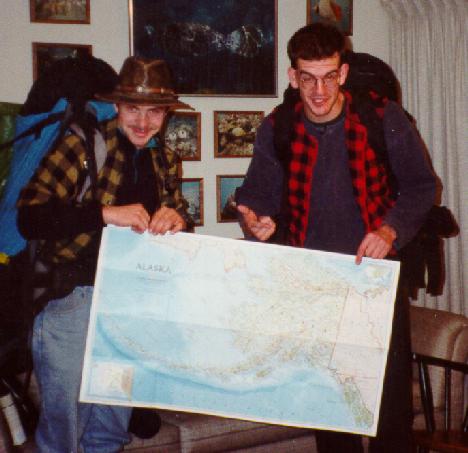

break, two things. First, there aren't many roads

on the Kenai peninsula (see map above) and

secondly, it's very safe --- so, no fretting at

home, Okay?)

So a half hour and a short drizzle gives way to

Mark, driving a pickup. He's about my age,

listening to a Rush album he loves. Not much to

say, except that Leif is his boss. Interesting how

that works, eh? I'm dropped off at a small town

gas station, where I meet Don. This is where the

story gets more interesting, so I'm going to take

a break for sleep.

Don seemed rather nonplused by life. Not that

he was depressed, or fundamentally unhappy

with it, but just that it wasn't serving up

anything tasty. My request for a ride in his

motor home was met with a sort of 'well, if I

gotta' look.

I eagerly hopped into the luxurious

accommodations of the aging motor home. At

about 40 feet, I suspected there was space for

luxury and the plush red swivel seat that met my

buttocks confirmed this. Enough luxury to

accommodate a 600 dollar bulldog as well. Bruno

didn't like the ride and his perpetual nervous

slobber over his owner's bedroll assured me that

Don's wet toes would drive home this fact over

the course of the night.

When I pointed this out to Don, he wasn't

surprised, commenting the trip makes Bruno

nervous. Bruno confirmed this by knocking his

cosmetics onto the floor. Having already

established that I recognized the importance of

and did indeed like the dog (an important ritual

for Alaskan guests and hitchhikers) I turned to

Don himself.

He was in his mid-late twenties and from

Michigan originally. A small gut (and overall

roundness) proved that Alaska's not the only

state with harsh winters. His overall demeanor

was to travel the world with, he was easy to talk

to, and as it was around 9:30 at night, that's all I

really wanted.

I had to admit that my talents for boosting

people's egos have increased dramatically, while

discussing college,

'Yeah, I never went.'

'Nothing wrong with that. Most people I know

shouldn't even have been there. You probably

made a better decision than they did.'

"Huh. It's true. Ya know, a lot of the guys that I

work with went to school and got psychology

degrees, and I earn the same amount of money."

"Yup. Some people just make the wrong choices."

Bearing in mind that Don's job was to pump

water out of the ground in order to lower the

water table to allow construction underground,

I'm suddenly glad that I had realized that being a

"people person" did not necessitate taking the

Major of the Masses. (I should probably thank

my parents.)

Well, Don got me to Kenai around 10:30. Arriving

in a gas station we met his other dog, a white lab

that had been chained to his truck all day

without food. It was so happy to see us that it

peed all over my shoe. That being, in these

formative years, a novel experience, I found it

funny. After much shenanigans, we drove the

two vehicles to a campsite where I spent a very

wet night in my tent. (No R.V. accommodations

were offered.)

Morning came and I shuffled to the curb,

overloaded, to practice my art. I had packed

nothing but Ramen and candy bars (we had

many on the boat) to eat on my journey. The

Ramen was gone the night before and the

snickers bar in my mouth offered little

sustenance. And lent less perseverance even, to

the task at hand. Half an hour of attempting to

flag a ride yielded nothing and in a desperate attempt

I even involved candy in my roadside shame.

It went something like this.

YOU! ME! (behind my back) REESES! Yum! Ride!

About half of the drivers laughed, some looked

vexed and one woman looked downright

offended. A diabetic? Just as I was giving up and

had turned away from the road, an old dirty

Cadillac El Dorado came to a dusty stop. And there

I met Vinnie the Pol[itician]. As I clumsily

stepped into the car the old man extended his

hand.

"Vincent Riley of Kenai. Pleased to meet you.

Where ya going?"

"Uh. Jos .. Claerbout --- Homer"

"Now, I gotta warn ya, kid. I'm a bullshitter and

a politician."

"I'm home. Let's go."

So we embarked on the hour long trip to Homer.

One, I may add, that was never interrupted with

silence. Politics and Economics were favorite

topics of Vinnie, and ones he spoke of with

authority. He had run for borough (equivalent

to county) mayor in '72 and managed to

summarize an article on derivatives for me he

had just pulled from the Economist. My

admission of a desire to work with the GAO met

not with a drooling blank stare, but rather his

own appraisal of the organization --- a

committee he's on was recently audited by them.

It was a great time --- the esoterics of academia

with all the comforts of home. Was this man in

enormous polyester pants my lost uncle?

Well,

we may never know as Homer proved too

painfully close for my newfound preferences.

He drove me though the town, relaying all the

gossip that was necessary to know,

and dropped me off on the Homer spit,

a 3 mile long peninsula no wider than 50 yards

that serves as the focal point

of drunken deadbeats and misplaced academics for the world.

I set up my tent.

I plopped down camp on the beach, alongside of

hundreds of others doing just the same. My first

thoughts of Homer were of excitement. So many

people, just like me, wanderers! Sharing a

lifestyle and an experience --- a whole mindset.

Unfortunately, my memories of Homer would be

marked by a different outlook --- but more on

that soon.

Despair and despondency

My first couple days in Homer I was so taken

back by the beauty and intrinsic relaxation that

I did little but lie around and go into town. But

how to get to town? I was 5 miles out (see map

above). (How I've failed to answer my true

calling as a cartographer is beyond me.) I

walked the first day. But that was something I

would not repeat. It was time to embrace the art

of hitching.

Thumbing it, part deux

Well, I wasn't even ready for the cavalcade of

characters a trip in the cab of a car would

reveal. I'm finding I don't appreciate people in

a psychological sense, but in a literary one. I

don't meet personalities --- I meet characters.

This is both an important realization and

distinction. Let me introduce to you (my pathetic

sense of prose striving here) a representative

sample of the people I've met.

Melissa

She seemed attractive behind her dark shades,

seated at the wheel of the battered pick-up. My

friendly offers to ride in the bed were refused,

she insisted there was room up front. We chatted

amiably for several minutes --- me self

conscious, unshowered, sporting a bandanna. As

we barreled down the spit, I noticed the sign

alerting campers to the self-registration office

and the daily fee of $3. I wondered aloud if I

should pay it.

"What do you mean, if? I'm the spitbitch".

"That what?"

"The spitbitch."

"How nice for you."

"No... I collect fees from the campers. Of course

you should register."

"Oh, damn."

Scott

"Hey, man, jump in!"

"Great, thanks!" Remembering my Alaska

etiquette, I knew my next question.

"What's the dog's name?"

"Riff, Oh, hey, there's another hitcher."

I nervously checked over my shoulder. The

decaying land cruiser seemed full, the back

being occupied by a Doberman-Rotweiler mix,

pleasant in spite of its heritage. As I scratched

the dog, the second hitcher filed into its domain,

secure as Scott had commanded, "Now, Riff, we

don't bite no hitchers."

After ascertaining that I was not a cop (I guess

he took my word for it), Scott produced a small

amount of marijuana which he sold to his

delighted passenger. (I politely abstained.)

Blaring Ozzy Osborne's "No more tears" loud

enough to wilt the ears of poor Riff, we tore

down the spit.

Billy

The truck was a relic. It rattled up the dirt road

toward me, obediently bowing to the side of the

path at the sight of my thumb. Billy met my

gaze. We got to talking. He told me of his first

winter in Alaska.

"Yeah, I didn't work. Just sat and drank. Went

through $30,000."

"Really, $30,000."

"Yeah, that's what I had after dealing coke in

Ohio."

"Coke, really."

"Yeah, it would have been another $40,000 but I

had an $800 a week crack habit."

"Really, $800?"

"Yeah, sometimes you can get a 100 dollar rock

and it'll last you all day."

"How nice." Suddenly we lurched to a stop. Billy

stared confused at the dashboard for a moment,

then laughed.

"Oh, we're in an automatic. Two pedals, not

three."

I decided to helpfully confirm his observation.

"Yes, two pedals."

He told me of his aspirations to be a baggage

handler this winter. I assured him he would

bring credibility to the profession.

Some woman whose name i do not know with red hair

I had walked three miles already to my

destination. Only about two were left. The blue

Saab had just passed me and I was growing more

frustrated. Then, 100 meters down the road, I

saw its reverse lights come on. It backed up all

the way, and to my incredulity the woman

invited me in.

"I'm only going a little bit, but I figured that was

better than nothing."

"Yeah ... I'm going to the Dry-dock."

"That's where I'm going." Her dog was named

Bud, an Australian Shepherd/Golden Retriever

mix (yes, I'm getting to really like dogs). We

shared a pleasant and laughing conversation for

10 minutes. Her hair was red, the dog was soft.

Okay, before anybody get concerned --- most of

the people I ride with are boring. Sometimes

they don't say anything. I just wanted to record

these characters in print.

On turning twenty homeless and unemployed

The day I turned twenty was a day of half

hearted job searching that yielded nothing. It

was a lonely day, and even a bit depressing. But

very illuminating. On it I realized that the Heist

of the Century is over. Anything I get from now

on I'm going to work damned hard for. To

expect the world to fall into my hands is to invite

failure. And I will not fail.

Failure

That was my only thought as I pounded the docks

4 times a day, looking for interested skippers

short a deckhand. Homer's number of fishing

boats seems large (although I'm sure it's tiny

compared to Kodiak). I came to know the docks

well. Many of the captains weren't on the boats,

but any that were would surely meet with my

query. The first man I talked to was interested in

hiring me. He never called. Three or four days

of this and I was getting down. But then, I was

hired on the Norquest, a 110 foot salmon tender.

Tenders pick up the fish at sea and deliver them

to the docks. It promised to be too good. I

enjoyed the company of the other three crew,

etc. Too good to be true.

Turns out the owner of the boat hired someone at

the same time the captain hired me. I was let go

with a great quantity of apologies and 50 bucks

for five hours work. This let down proved great.

I sat in my tent the next day and just felt sorry

for myself. Would I have to go to Kodiak? Should

I work in a cannery? Why don't I get a real job?

Will I have enough money to live here next

year? I ruminated on these questions, while

lamenting my pathetic situation. But then I

remembered my birthday.

"If I'm going to fail, fine. But I refuse to fail

sitting on my ass. If I fail, it won't be for the

lack of trying." So the next day I walked the

entire length of the docks, even those piers that

had mostly charters and sport fishermen. I

asked every captain I saw, no excuses this time.

Nothing the first day. Nothing the second day.

On the third day, just as I was walking down the

last pier, a voice called out. It was Todd, from the

Endeavor. I have been persistent with his boss,

Leroy, about a job. None had come. It appears

that now Todd knows someone who doesn't have

a crew. He was in Drydock. I thanked Todd

profusely and prepared to head out the next day.

That night I felt good.

Things get out of control

I hitched the five mile ride to the Drydock, half

of it was unpaved. The trip allowed me to see a

beautiful side of Alaska I had forgotten. Living

on the beach, I had forgotten the lush forests

and beautiful scenery Alaska has to offer. I

think I may live this `isolation' next year.

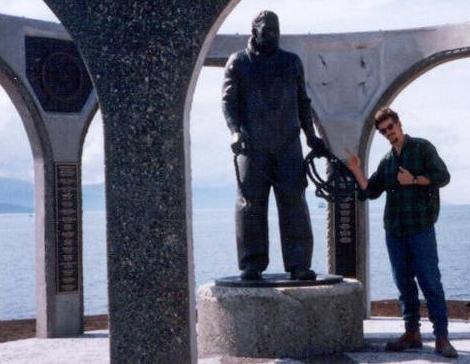

Arriving in Drydock, I scooped out the 32' seiner

"Omega" and its skipper,

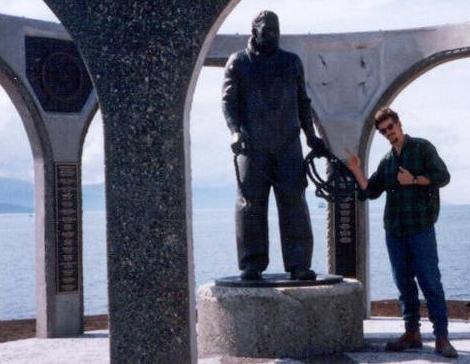

Brad Chisholm.

[photo taken later by parents]

I found him, working in the engine hold of the

tiny boat (32 feet is a very small seiner --- most

tend to be 40-45 feet long, the limit is currently

58). He actually seemed interested in

interviewing me, something I welcomed,

hurling up questions, as his mind strived to fix

the hydraulic pump at the same time it assessed

this newcomer. After a few minutes he surfaced

and told me,

"You're the first one to show up, so I'll probably

hire you. Come back tomorrow at nine."

I was elated. I even went out and bought lunch

for the first time in two weeks. Hitching back, I

met Don Flynn, captain of the Lady Lee, a 46 foot

seiner going down to Valdez the 10th of July.

"Yeah", he said, "I'm looking for a crew.

Experience doesn't matter." "Really."

I found it hard to believe. Although

the 10th was a bit late for my taste (it was

currently the 23rd) I gladly took his phone

number, keeping my options open. Once back

in town I decided to check on my other lead, Ron

White of the Middy. He confirmed he too was

looking for a crew, although he was going to

miss a crucial week in July. And then, in the

bookstore, a fisherman walks in and starts

lamenting how he just lost his deckhand and

needs one immediately. It was odd.

After much thought, I decided to stay with Brad.

As I have to hitch two rides to get to the Drydock,

I talk to a lot of fishermen. All of them know

Brad, and all of them respect him, both as a nice

guy and as a fisherman. Even though we don't

go out till tomorrow, I know I've made the right

choice.

End Journal part 1 --- sent to parents 6/26/94.

Well, this is the first installment --- an anemic

34 pages. Expect more soon, some of this writing

is good, and some is crap. Plow through what

you can. I'm probably at sea now and will call as

soon after the 3rd as I can.

Love,

Jos

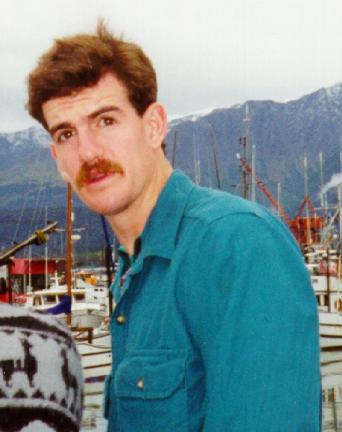

Between fishing jobs

and at the end of the summer

he was a volunteer

at

KBBI radio station in Homer,

shown here with Mums and a KBBI coffee cup.

He only owned 10% of the

Big fish.

When the boat's owner realized what they had on, he got out his rifle ---

taking no chances on losing it.

Other Jos Alaska links:

Big fish.

Audio tape diary.

Election campaign.

American Country Magazine.

Mine guiding.

Fishing diary.

return to the Life of Jos

5/23/94

We arrived in Anchorage around two in the

afternoon on Friday. Our initial excitement and

plans to "just pitch our tent outside the airport",

were dampened somewhat by the information

woman's insistence that Alaska isn't "just one big

wilderness area." As we sat in the airport the theme

that would soon repeat itself sunk into our heads,

"we have no plan, we have no plan." Would

misery exist without expectations? It was soon

ascertained that money would have to be spent

(and after our pre-departure splurge, this wasn't

appealing to either of us) and the local youth

hostel came up as the winner. In economics, the

concept of an externality is defined as something

that arises out of an activity that affects a third

party in a way not necessarily intended. They

can be positive (you like listening to the local

school band practice) or negative (like

pollution). Youth hostels are an excellent

example of something that can yield positive

externalities. Put a bunch of travelers together

in a very small place and guess what? They

exchange information. It was quickly

discovered that our initial destination, Homer,

was full of people like ourselves (clueless,

unemployed) and that Seward was really our best

bet.

5/23/94

We arrived in Anchorage around two in the

afternoon on Friday. Our initial excitement and

plans to "just pitch our tent outside the airport",

were dampened somewhat by the information

woman's insistence that Alaska isn't "just one big

wilderness area." As we sat in the airport the theme

that would soon repeat itself sunk into our heads,

"we have no plan, we have no plan." Would

misery exist without expectations? It was soon

ascertained that money would have to be spent

(and after our pre-departure splurge, this wasn't

appealing to either of us) and the local youth

hostel came up as the winner. In economics, the

concept of an externality is defined as something

that arises out of an activity that affects a third

party in a way not necessarily intended. They

can be positive (you like listening to the local

school band practice) or negative (like

pollution). Youth hostels are an excellent

example of something that can yield positive

externalities. Put a bunch of travelers together

in a very small place and guess what? They

exchange information. It was quickly

discovered that our initial destination, Homer,

was full of people like ourselves (clueless,

unemployed) and that Seward was really our best

bet.

Our campsite was shared by four other tents all

of which would be gone by morning. Had we

known what was in store, we might have done

the same. So there we were, standing utterly

rain proof, wondering how our current situation

would translate into a like one inside of our

tents.

Our campsite was shared by four other tents all

of which would be gone by morning. Had we

known what was in store, we might have done

the same. So there we were, standing utterly

rain proof, wondering how our current situation

would translate into a like one inside of our

tents.

All in all, though mortality rates dropped to

about 25% with my more personalized service.

And one last note on junk fish -- skates. They're

the ugliest damn fish I've seen in my life. Here,

I'll try to draw the underside of one for you.

All in all, though mortality rates dropped to

about 25% with my more personalized service.

And one last note on junk fish -- skates. They're

the ugliest damn fish I've seen in my life. Here,

I'll try to draw the underside of one for you.