|

|

|

|

Visualization and data reordering using EcoRAM |

Using this template, the transpose algorithm can be written in a push (loop

over input) or pull (loop over output) manner. For EcoRAM , and in many other

cases (such as wanting to pipe the output), the pull method is more efficient.

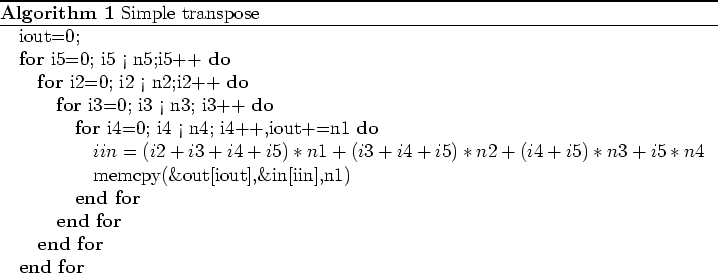

The basic transpose algorithm using the five dimensional template then

takes the following form.

![]()

This simple algorithm assumes that you can hold both the input and

output matrices in RAM. A problem with this simple approach is the

very poor use of input cache lines for small  .

.

If we can hold ![]() is memory we can get acceptable performance

with either algorithm 4 or slight modification

that processes each

is memory we can get acceptable performance

with either algorithm 4 or slight modification

that processes each ![]() block in turn. We could still use the

basic template for large problems by mmapping the input and output file but

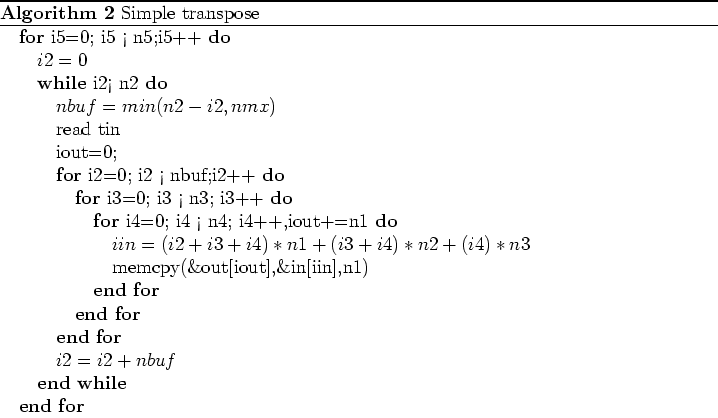

the cache miss problem would be further exacerbated. A better alternative

is to introduce two temporary buffers, tin and tout. These buffers

are of size

block in turn. We could still use the

basic template for large problems by mmapping the input and output file but

the cache miss problem would be further exacerbated. A better alternative

is to introduce two temporary buffers, tin and tout. These buffers

are of size ![]() , where

, where ![]() is chosen so that the combined

size of tin and tout does not exceed DRAM

is chosen so that the combined

size of tin and tout does not exceed DRAM![]() . The buffered algorithm

then takes the following form.

. The buffered algorithm

then takes the following form.

![]()

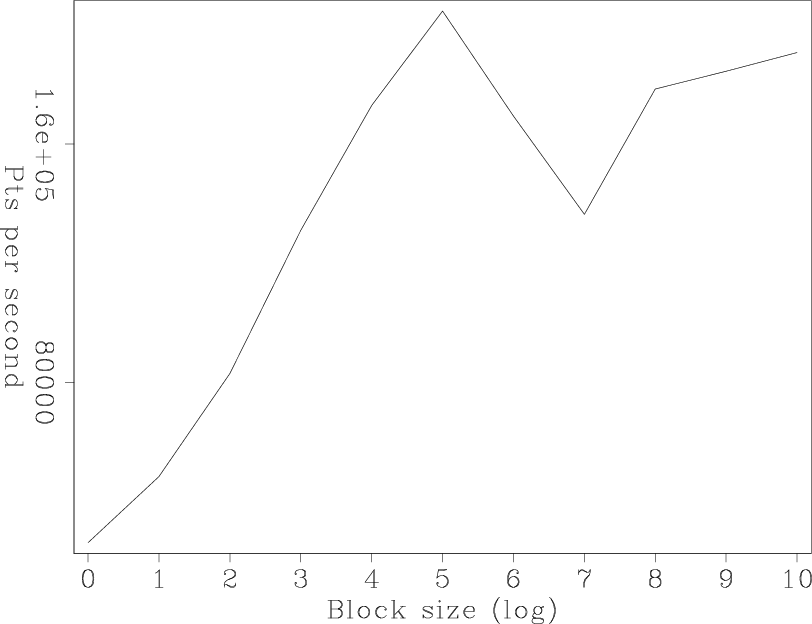

The larger ![]() , the better the performance. Figure 1 shows that even

a RAM-based system benefits from the buffered approach. Note how we can

gain a performance advantage of greater than six with larger

, the better the performance. Figure 1 shows that even

a RAM-based system benefits from the buffered approach. Note how we can

gain a performance advantage of greater than six with larger  sizes.

sizes.

|

ram

Figure 1. The number of elements per second vs |

|

|---|---|

|

|

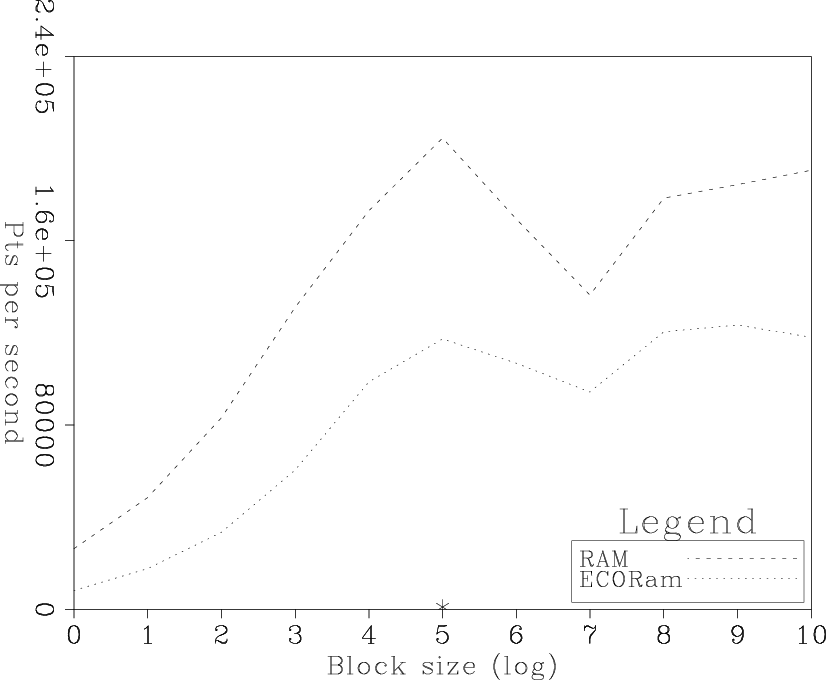

Figure 2 compares the performance of EcoRAM versus RAM. Note the

similarity of the two curves. The `*' in the figure shows the comparable

disk approach. The disk approach is ![]() th speed of the slowest

EcoRAM result and

th speed of the slowest

EcoRAM result and ![]() th the optimal buffer choice.

th the optimal buffer choice.

|

disk

Figure 2. The number of elements per second vs. |

|

|---|---|

|

|

As a final test, we transposed a float dataset of size

![]() switching

axes 1,2 with axis 5. Using the buffered approach of

algorithm 5, a conventional disk took 1293 minutes (using

an intermediate buffer size of 1 GB) while the same

dataset took 22 minutes using EcoRAM , a

switching

axes 1,2 with axis 5. Using the buffered approach of

algorithm 5, a conventional disk took 1293 minutes (using

an intermediate buffer size of 1 GB) while the same

dataset took 22 minutes using EcoRAM , a ![]() performance improvement.

performance improvement.

|

|

|

|

Visualization and data reordering using EcoRAM |