|

|

|

|

Velocity model evaluation through Born modeling and migration: a feasibility study |

To test the feasibility of the method outlined above, we designed two simple synthetic test cases: a single flat reflector in the subsurface (Figure 2(a)), and a single reflector dipping at  (Figure 2(b)). We restricted these initial test cases to a single reflector in order to avoid problems related to crosstalk between multiple events or reflectors; while there are methods to attenuate this crosstalk, we hoped to gauge the feasibility of the method using only a single shot to migrate the Born-modeled data, without sophisticated phase-encoding schemes.

(Figure 2(b)). We restricted these initial test cases to a single reflector in order to avoid problems related to crosstalk between multiple events or reflectors; while there are methods to attenuate this crosstalk, we hoped to gauge the feasibility of the method using only a single shot to migrate the Born-modeled data, without sophisticated phase-encoding schemes.

|

|---|

|

flat-sp,dip-sp

Figure 3. Isolated image points from Figures 2(a) and 2(b) used for the modeling procedure. The points are separated by twice the maximum subsurface offset value in order to avoid crosstalk artifacts in the modeling. |

|

|

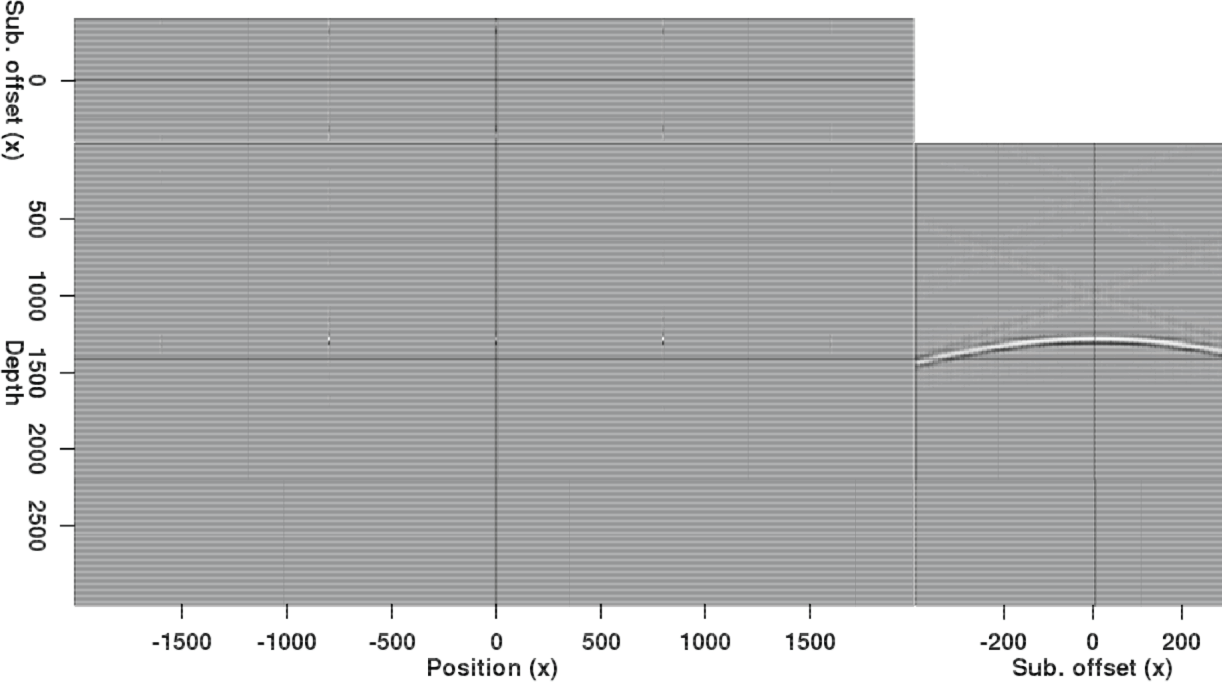

Both examples in Figure 2 were generated by migrating with an incorrect velocity model (15% slower than the constant-velocity model used to generate the original dataset). The effects of using an incorrect velocity can be seen clearly on the subsurface offset gather (non-focused event). A key goal of our Born modeling procedure is to replicate this behavior when the same velocity model is used to migrate the Born-modeled data. To test this, we sample isolated points from the reflectors in Figure 2, and use these points to generate the areal source function described in the previous section. In order to avoid unwelcome crosstalk between these points during the modeling process, they are separated by a distance that is twice the maximum subsurface offset, as seen in Figure 3.

|

|---|

|

flat-sp-born,dip-sp-born

Figure 4. Migrated images after Born modeling using the images in Figure 3 as the reflectivity model. Although the amplitudes differ, the kinematics of the events in both figures match. |

|

|

Once the source function is ``recorded," Born modeling is performed using the sub-sampled images in Figure 3 as reflectivity models. The results of migrating this Born-modeled data, using the same velocity model used to produce the images in Figure 2, are seen in Figure 4. Because these images were migrated using an areal source function, only a single shot was necessary; this means that the images in Figure 4 were produced in seconds, nearly three orders of magnitude less time than was necessary to compute the images in Figure 2. Comparing the subsurface offset gathers for both of these figures, we see that while amplitudes differ, the kinematics have been accurately preserved in the Born-modeled result. If our goal is to evaluate the velocity model used, the quickly-obtained results in Figure 4 should be sufficient.

The importance of correctly spacing the image points we use for the modeling is illustrated in Figure 5. Here, points from the flat reflector image in Figure 2(a) have been sampled twice as frequently, at a spacing equal the maximum subsurface offset. Figure 5 shows the result of using these points to create the areal source function, and then performing Born modeling and migration as before. Now, crosstalk between the closely-spaced image points results in severe artifacts, including spurious events on the zero-subsurface offset image.

|

|---|

|

flat-xtalk

Figure 5. Migration result if the image points sampled from Figure 2(a) are spaced at less than twice the maximum subsurface offset. Crosstalk artifacts dominate the image, making interpretation extremely difficult. |

|

|

As mentioned in the previous section, an advantage of this Born modeling strategy is that the synthesized data may be recorded at any depth, effectively re-datuming wavefields prior to migration. This can lead to significant computational savings, especially if velocities are well known until a certain depth. To verify that this capability does not effect the accuracy of migration results, we recorded both the areal source wavefield and the Born-modeled data at depth ![]() , instead of at the surface. Figure 6 shows the result of migrating this data in the dipping reflector case. Comparison with Figure 4(b) confirms that the two results are virtually identical for the area of interest.

, instead of at the surface. Figure 6 shows the result of migrating this data in the dipping reflector case. Comparison with Figure 4(b) confirms that the two results are virtually identical for the area of interest.

|

|---|

|

dip-short

Figure 6. Migration result using Born-modeled data from the model in Figure 3(b). In this case, the synthesized data was recorded in the subsurface instead of on the surface, effectively re-datuming the wavefields. |

|

|

Finally, we wish to test the ultimate purpose of this method: quickly evaluating multiple velocity models. Once the Born-modeled dataset has been synthesized, we can use any velocity model to image the data. Again, we are able to perform these migrations very quickly, on the order of seconds for the examples here. Figure 7 compares the results of using three different velocity models to image the Born-modeled data: one that is 5% slower than the true velocity (Panel a); one that is exactly the true velocity (Panel b); and one that is 5% faster than the true velocity (Panel c). From these results, it is clear that the velocity model used to produce Panel b's result is the most accurate - the subsurface offset gather is flat and relatively focused, and, unlike Panels a and c, there are no signs of over- or under-migration on the zero-subsurface offset image. Because the velocity differences between these three models are relatively small, this is an encouraging sign that this method can ultimately allow us to quickly test more complex models for both synthetic and field data.

|

|---|

|

comp-slow,comp-act,comp-fast

Figure 7. Result of migrating the Born-modeled data with (a) 5% too slow velocity; (b) correct velocity; and (c) 5% too fast velocity. Each migration was nearly instantaneous, and the effects of the different velocity models are readily apparent. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Velocity model evaluation through Born modeling and migration: a feasibility study |