|

|

|

|

Interpreter input for seismic image segmentation |

| (2) |

is the amplitude value at point

is the amplitude value at point

|

|---|

|

o3d-far

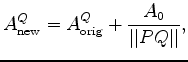

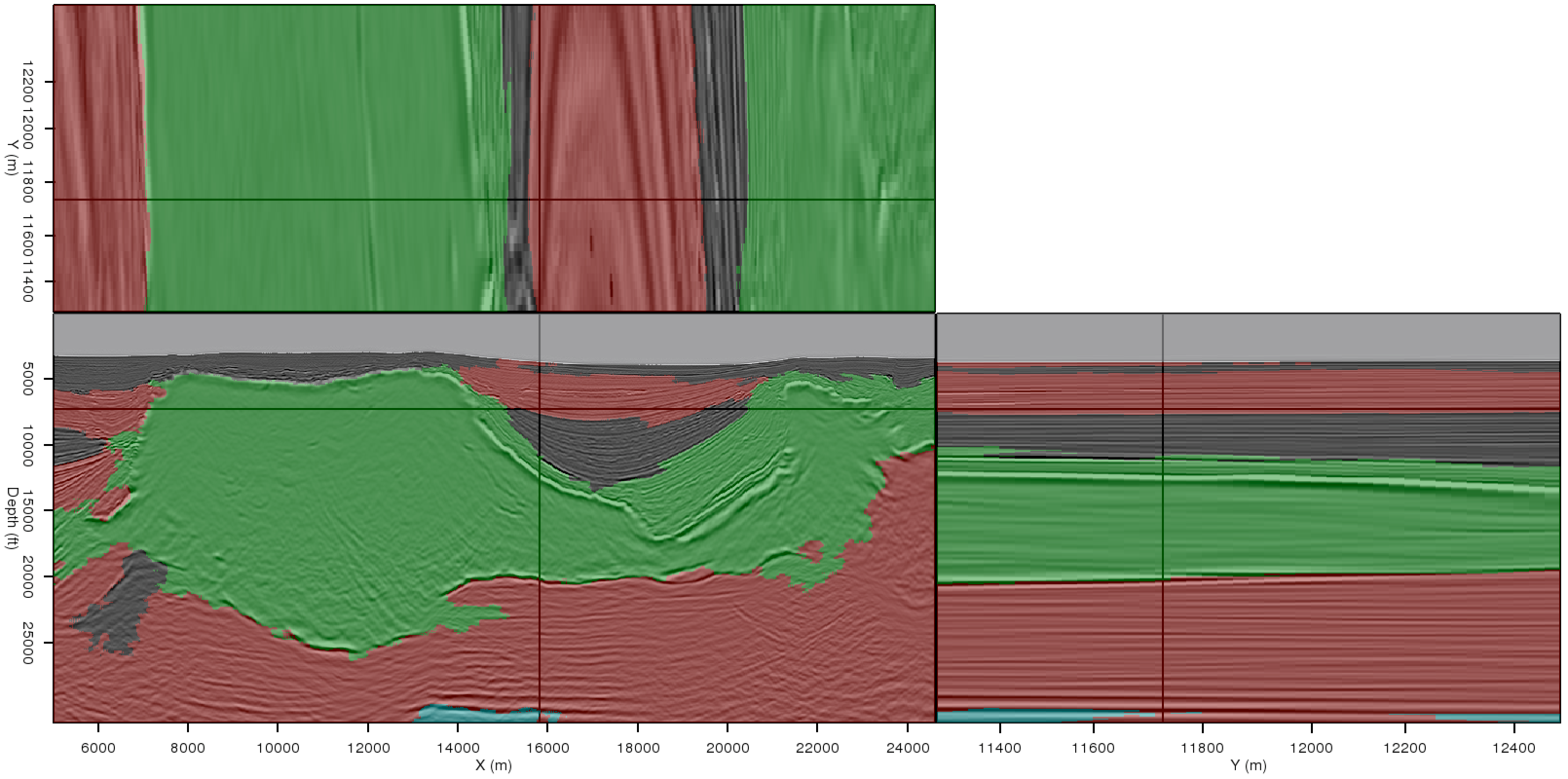

Figure 9. Slices from the 3D image cube far away from any interpreter-supplied salt picks. |

|

|

|

|---|

|

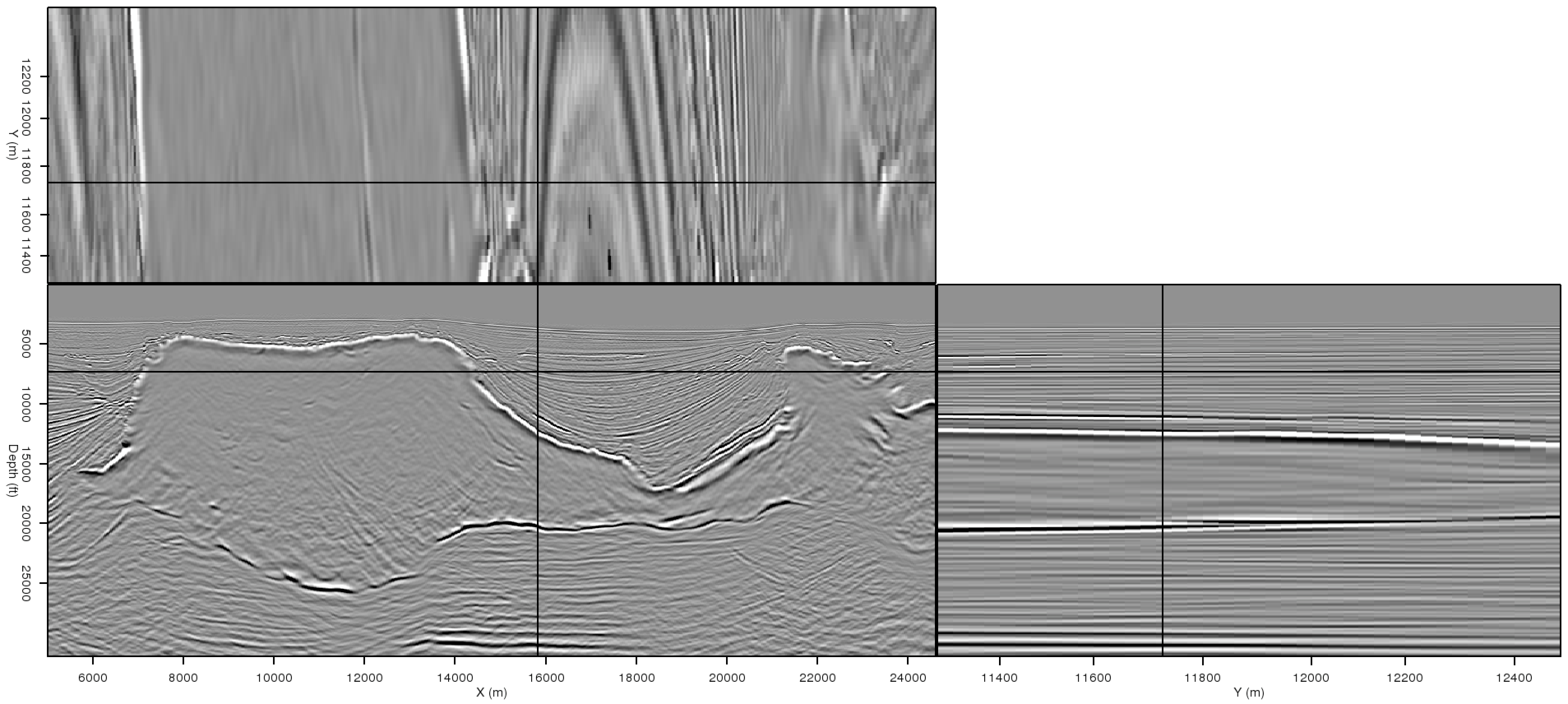

o3d-env-orig-far,o3d-env-new-far

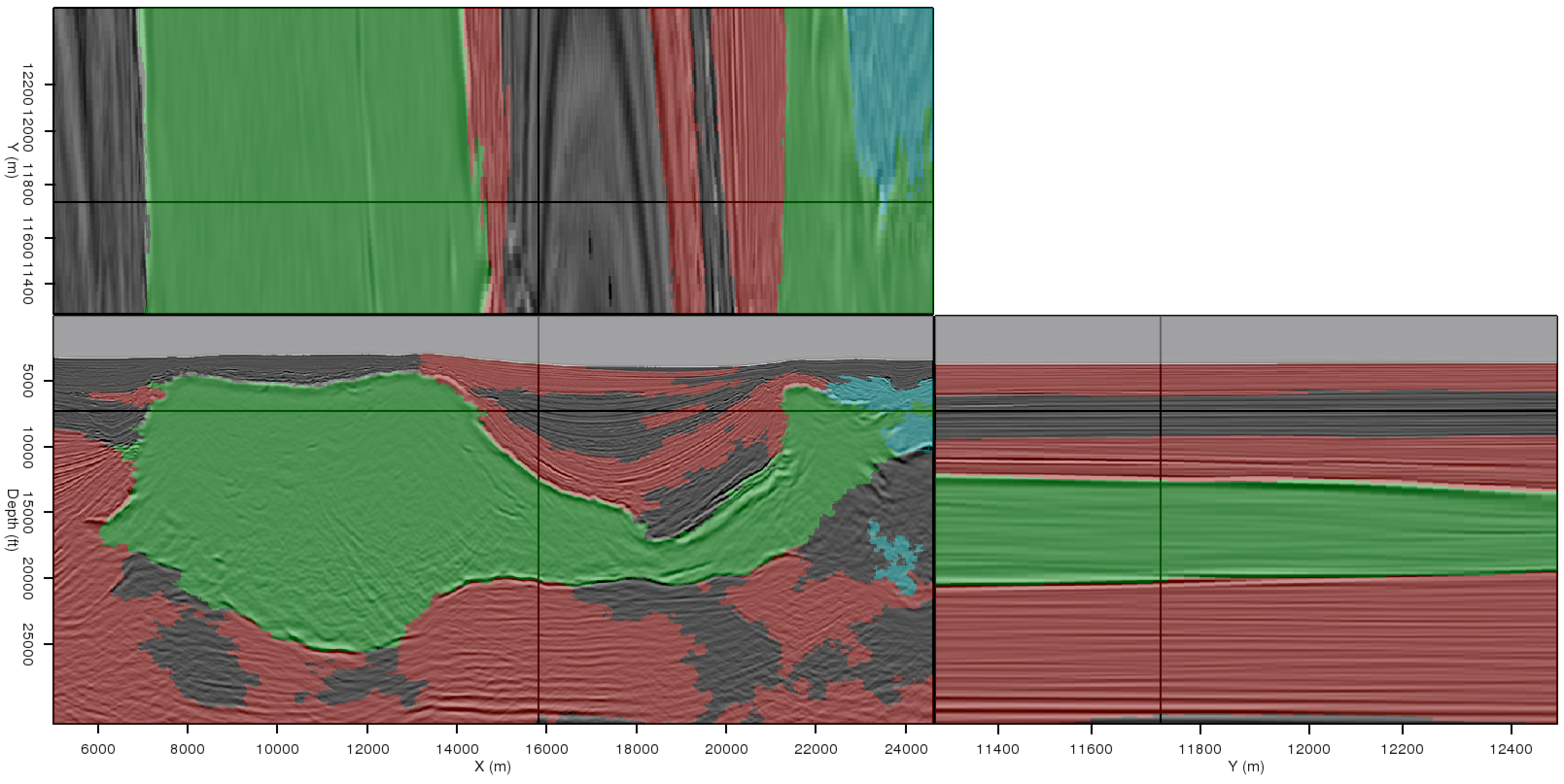

Figure 10. Envelope volumes at the position of the image slices seen in Figure 9, (a) before and (b) after incorporating interpreter input from a distant location. In (b), continuity of the salt boundary is improved, allowing a more accurate segmentation result. |

|

|

|

|---|

|

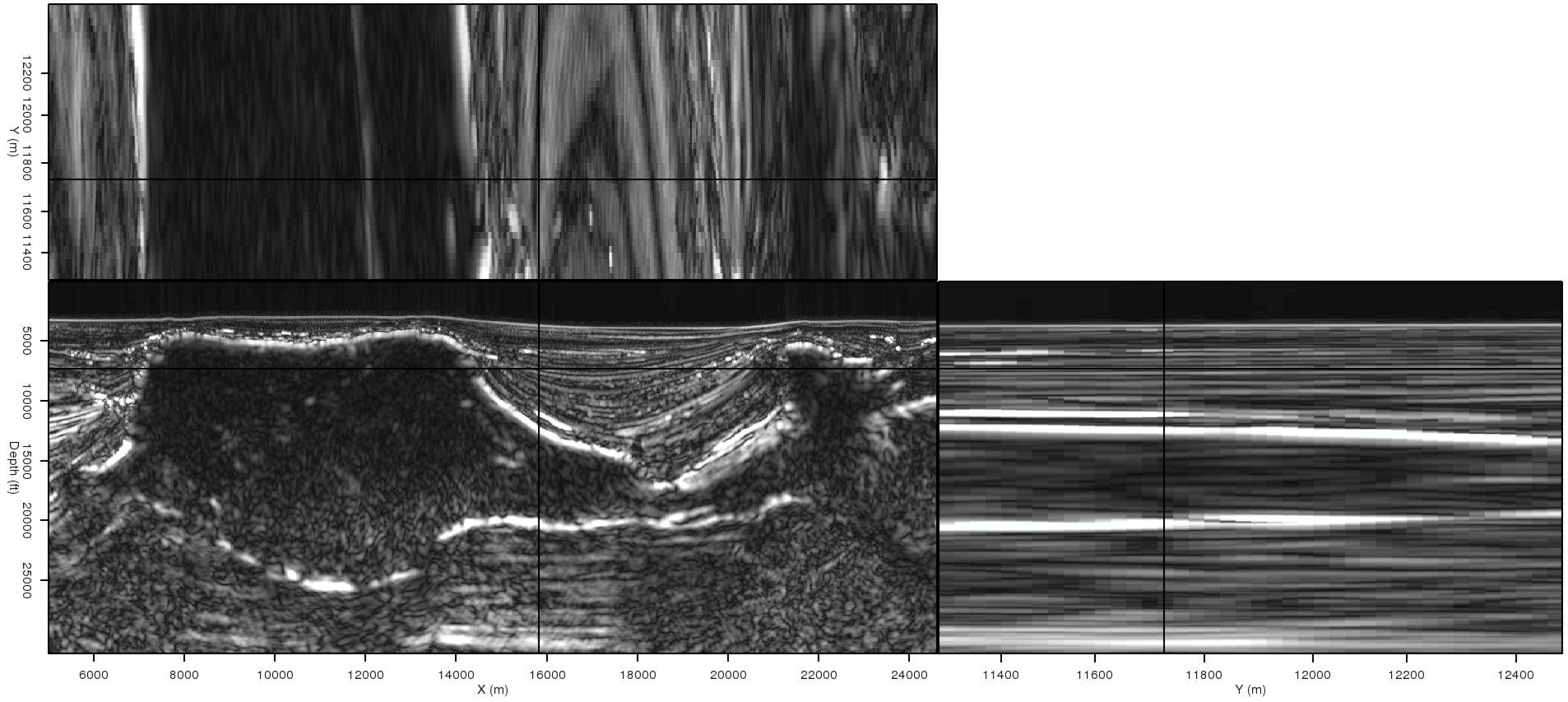

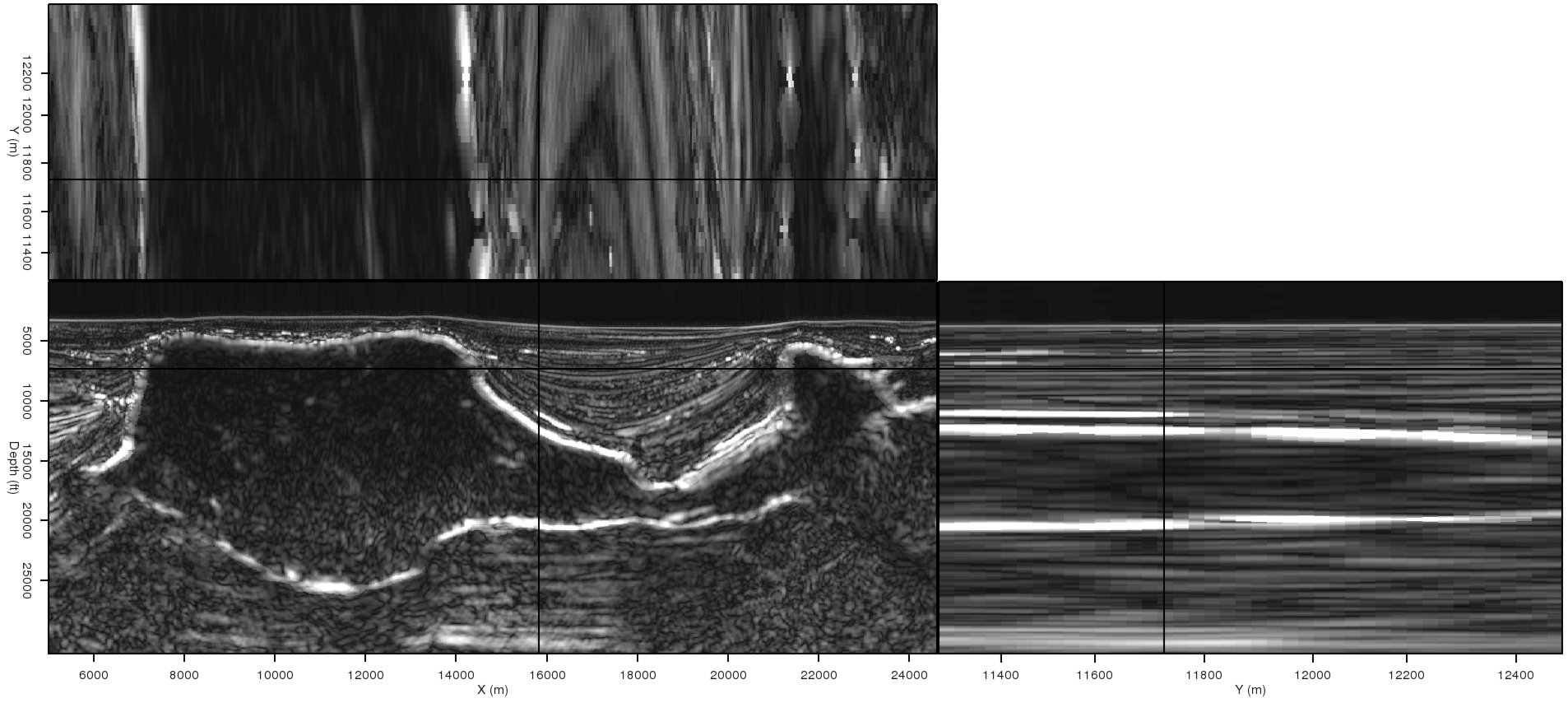

3d-origseg-far,3d-newseg-far

Figure 11. A comparison of segmentation results (a) without using interpreter input, and (b) after incorporating information from the picks in Figure 5(b). Even though the data slices shown here are far from the location of the manual picks, the strategy of spreading information from 2D picks into the third dimension allows for a much more accurate result in (b). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Interpreter input for seismic image segmentation |