|

|

|

|

Phase encoding with Gold codes for wave-equation migration |

Linear feedback shift registers (LFSR) (Moon and Stirling, 2000) are called state machines, whose components and functions are:

In number theory, Galois fields (![]() ) are finite fields in which all operations result in an element of the field (Lidl and Niederreiter, 1994). Addition, subtraction and multiplication of polynomials are defined in a finite field. Module 2 arithmetic forms the basis of

) are finite fields in which all operations result in an element of the field (Lidl and Niederreiter, 1994). Addition, subtraction and multiplication of polynomials are defined in a finite field. Module 2 arithmetic forms the basis of

![]() (Galois field of order 2). Addition and multiplication operations in GF(2) can be represented by bitwise operators XOR and AND, respectively. Table 2 synthesizes the possible output values of addition and multiplication over

(Galois field of order 2). Addition and multiplication operations in GF(2) can be represented by bitwise operators XOR and AND, respectively. Table 2 synthesizes the possible output values of addition and multiplication over

![]() .

.

If a polynomial can not be represented as the product of two or more polynomials, it is called an irreducible polynomial. For instance, ![]() is irreducible over

is irreducible over

![]() because it can not be factored. However,

because it can not be factored. However, ![]() is not irreducible over

is not irreducible over

![]() because, using normal algebra,

because, using normal algebra,

![]() , and after reduction module-2, is

, and after reduction module-2, is ![]() (the term

(the term ![]() is dropped). So, in

is dropped). So, in

![]() ,

,

![]() .

.

The importance of studying irreducible polynomials

![]() is that they are used to represent tap sequences. Considering an irreducible polynomial, the corresponding tap sequence is given by the exponents of the terms with coefficients of 1 (Dinan and Jabbari, 1998). Special tap sequences can be used to generate particular pseudo-random binary sequences. They are called maximum length sequences (m-sequences) and, by definition, are the largest codes that can be generated by a LFSR for a given tap sequence. Their length is

is that they are used to represent tap sequences. Considering an irreducible polynomial, the corresponding tap sequence is given by the exponents of the terms with coefficients of 1 (Dinan and Jabbari, 1998). Special tap sequences can be used to generate particular pseudo-random binary sequences. They are called maximum length sequences (m-sequences) and, by definition, are the largest codes that can be generated by a LFSR for a given tap sequence. Their length is ![]() , where

, where ![]() is the number of elements of the tap sequence, and

is the number of elements of the tap sequence, and

![]() .

.

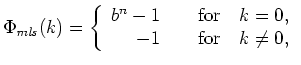

The autocorrelation function of an m-sequence,

![]() , is given by

, is given by

is the lag of correlation.

In spite of the good autocorrelation properties, m-sequences, in general, are not immune to cross-correlation problems, and they may have large and unpredictable cross-correlation values. However, the so-called preferred pairs of m-sequences have cross-correlation functions which might assume the predicted values,

is the lag of correlation.

In spite of the good autocorrelation properties, m-sequences, in general, are not immune to cross-correlation problems, and they may have large and unpredictable cross-correlation values. However, the so-called preferred pairs of m-sequences have cross-correlation functions which might assume the predicted values,

|

|---|

|

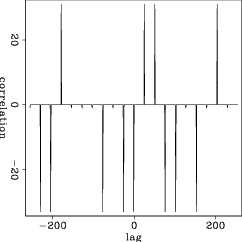

prefpairs

Figure 1. Cross-correlation of a m-sequences that form a preferred pair. |

|

|

The number of possible preferred pairs of m-sequences is limited, when compared to the requirements of practical applications of wireless communication. Preferred pairs of m-sequences, however, are used to generate Gold codes (Dinan and Jabbari, 1998).

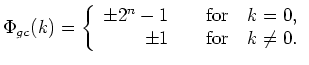

In CDMA, Gold codes are used as chipping sequences that allow several callers to use the same frequency, resulting in less interference and better utilization of the available bandwidth. Originally proposed by Gold (1967), Gold codes can be computed by module-2 addition (

![]() ) of circularly shifted preferred pairs of m-sequences of length

) of circularly shifted preferred pairs of m-sequences of length ![]() . The autocorrelation function of a Gold code,

. The autocorrelation function of a Gold code,

![]() , is given by

, is given by

, is given by

, is given by

is given by the difference between the number of circular shifts applied to the m-sequence to compute the Gold codes.

is given by the difference between the number of circular shifts applied to the m-sequence to compute the Gold codes.

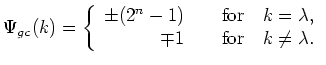

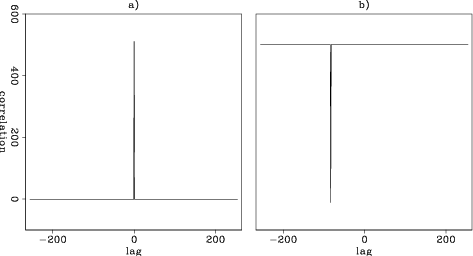

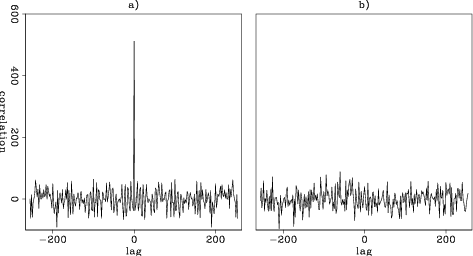

Figure 2 illustrates the correlation properties of the Gold codes. The left part shows the autocorrelation of the Gold code generated with one circular shift of the preferred pair of m-sequence. The right part shows the cross-correlation of the Gold code generated with one circular shift of the preferred pair of m-sequence with the Gold code generated with 84 circular shifts. Note that the peak of the cross-correlation occurs at lag 84. For comparison, we show the correlation functions of conventional random codes in Figure 3. The autocorrelation function presents nearly periodic side lobes with additive low-amplitude random variations. The peak-to-side lobe ratio is around 30. The cross-correlation function is pseudo-random, and its amplitudes are of the same order of magnitude as those of the non-zero lags of the autocorrelation function.

|

|---|

|

gold184

Figure 2. Correlation functions of Gold codes. a) Autocorrelation of Gold code generated with one circular shift of the preferred pair of m-sequence. b) Cross-correlation of the Gold code generated with one circular shift of the preferred pair of m-sequence with that generated with 84 circular shifts. The peak of the cross-correlation occurs at lag -84. |

|

|

|

|---|

|

rand

Figure 3. Correlation functions of conventional random codes. a) Autocorrelation of the conventional random code. b) A cross-correlation. |

|

|

After computing Gold codes, we use their phase information to encode the modeling experiments.

|

|

|

|

Phase encoding with Gold codes for wave-equation migration |