|

|

|

| Two point raytracing for reflection off a 3D plane |  |

![[pdf]](icons/pdf.png) |

Next: APPENDIX B

Up: APPENDIX A

Previous: APPENDIX A

From Lanczos (1956),

pages 6-8, 19-22:

3. Cubic equations.

Equations of third and fourth order are still solvable by algebraic

formulas. However, the numerical computations required by the

formulas are usually so involved and time-absorbing that we prefer

less cumbersome methods which give the roots in approximation

only but still close enough for later refinement.

The solution of a cubic equation (with real coefficients) is

particularly convenient since one of the roots must be real.

After finding this root, the other two roots follow immediately

by solving a quadratic equation.

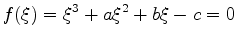

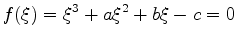

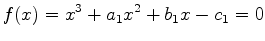

A general cubic equation can be written in the form

. . |

|

The factor of  can always be normalized to 1 since we can

divide through by the highest coefficient. Moreover, the absolute

term can always be made negative because, if it is originally

positive, we put

can always be normalized to 1 since we can

divide through by the highest coefficient. Moreover, the absolute

term can always be made negative because, if it is originally

positive, we put

and operate with

and operate with  .

.

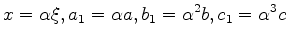

Now it is convenient to introduce a new scale factor which will

normalize the absolute term to  . We put

. We put

and write the new equation

If we choose

we obtain

Now, since  is negative and

is negative and

is positive, we know

that there must be at least one root between

is positive, we know

that there must be at least one root between  and

and  .

We put

.

We put  and evaluate

and evaluate  . If

. If  is positive, the root

must be between 0

and

is positive, the root

must be between 0

and  ; if

; if  is negative, the root must

be between

is negative, the root must

be between  and

and  . Moreover, since

. Moreover, since

we know in advance that we cannot have three roots

between 0

and  , or

, or  and

and  . Hence if

. Hence if  ,

we know that there must be one and only one real root

in the interval

,

we know that there must be one and only one real root

in the interval ![$ [ 0 , 1 ]$](img132.png) , while if

, while if  , we know

that there must be one and only one real root in the interval

, we know

that there must be one and only one real root in the interval

![$ [1 , \infty]$](img134.png) . The latter interval can be changed to the interval

. The latter interval can be changed to the interval

![$ [1,0]$](img135.png) by the transformation

by the transformation

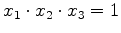

which simply means that the coefficients of the equation change

their sequence:

Hence we have reduced our problem to the new problem:

find the real root of a cubic equation in the range ![$ [ 0 , 1 ]$](img132.png) .

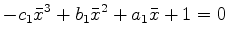

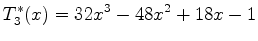

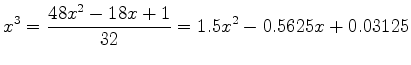

We solve this problem in good approximation by taking advantage of

the remarkable properties of the Chebyshev polynomials (cf. VII, 9)

which enable us to reduce a higher power to lower powers with

a small error. In particular, the third Chebyshev polynomial

.

We solve this problem in good approximation by taking advantage of

the remarkable properties of the Chebyshev polynomials (cf. VII, 9)

which enable us to reduce a higher power to lower powers with

a small error. In particular, the third Chebyshev polynomial

normalized to the range ![$ [ 0 , 1 ]$](img132.png) gives

gives

with a maximum error of

. The original cubic

is thus reducible to a quadratic with an error not exceeding

. The original cubic

is thus reducible to a quadratic with an error not exceeding

.

.

We now solve this quadratic, retaining only the root between

0

and  .

.

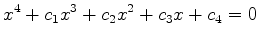

11. Equations of fourth order.

Algebraic equations of fourth order with generally complex roots

occur frequently in the stability analysis of airplanes and in problems

involving servomechanisms.

The historical method of solving algebraic equations of fourth order

(also called biquadratic or quartic equations) involves the following

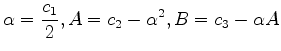

steps. By a transformation of the form

the coefficient

of the cubic term is annihilated. Then an auxiliary cubic equation

is solved. The roots of the original equation are constructed with

the help of the three roots of the auxiliary cubic. Numerically

this method is lengthy and cumbersome. The following modification

of the traditional procedure yields the four roots of an arbitrary

quartic equation with real coefficients on the basis of a quick

and numerically convenient scheme.

the coefficient

of the cubic term is annihilated. Then an auxiliary cubic equation

is solved. The roots of the original equation are constructed with

the help of the three roots of the auxiliary cubic. Numerically

this method is lengthy and cumbersome. The following modification

of the traditional procedure yields the four roots of an arbitrary

quartic equation with real coefficients on the basis of a quick

and numerically convenient scheme.

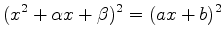

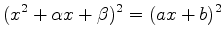

Every equation of the form

can be rewritten as follows:

. . |

|

If the original  are real, the new coefficients are also real.

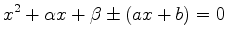

Hence the original equation becomes solvable in the form of the

quadratic equation

are real, the new coefficients are also real.

Hence the original equation becomes solvable in the form of the

quadratic equation

which has four (generally complex) roots, obtainable by the standard

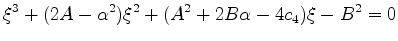

formula. The new coefficients can be determined as follows. We

evaluate in succession the following numerical constants:

and form the cubic equation

Since the left side is negative at  , a positive real root

must exist. We determine this root according to the method of § 3.

In order to avoid later corrections, it is advisable to add at this point

Newton's correction (cf. § 5), obtaining

, a positive real root

must exist. We determine this root according to the method of § 3.

In order to avoid later corrections, it is advisable to add at this point

Newton's correction (cf. § 5), obtaining  with great accuracy.

The coefficients of the reduced equation are then determined as follows:

with great accuracy.

The coefficients of the reduced equation are then determined as follows:

|

|

|

| Two point raytracing for reflection off a 3D plane |  |

![[pdf]](icons/pdf.png) |

Next: APPENDIX B

Up: APPENDIX A

Previous: APPENDIX A

2012-10-29

.

. can always be normalized to 1 since we can

divide through by the highest coefficient. Moreover, the absolute

term can always be made negative because, if it is originally

positive, we put

can always be normalized to 1 since we can

divide through by the highest coefficient. Moreover, the absolute

term can always be made negative because, if it is originally

positive, we put

and operate with

and operate with  .

.

. We put

. We put

is negative and

is negative and

is positive, we know

that there must be at least one root between

is positive, we know

that there must be at least one root between  and

and  .

We put

.

We put  and evaluate

and evaluate  . If

. If  is positive, the root

must be between 0

and

is positive, the root

must be between 0

and  ; if

; if  is negative, the root must

be between

is negative, the root must

be between  and

and  . Moreover, since

. Moreover, since

, or

, or  and

and  . Hence if

. Hence if  ,

we know that there must be one and only one real root

in the interval

,

we know that there must be one and only one real root

in the interval ![$ [ 0 , 1 ]$](img132.png) , while if

, while if  , we know

that there must be one and only one real root in the interval

, we know

that there must be one and only one real root in the interval

![$ [1 , \infty]$](img134.png) . The latter interval can be changed to the interval

. The latter interval can be changed to the interval

![$ [1,0]$](img135.png) by the transformation

by the transformation

![$ [ 0 , 1 ]$](img132.png) .

We solve this problem in good approximation by taking advantage of

the remarkable properties of the Chebyshev polynomials (cf. VII, 9)

which enable us to reduce a higher power to lower powers with

a small error. In particular, the third Chebyshev polynomial

.

We solve this problem in good approximation by taking advantage of

the remarkable properties of the Chebyshev polynomials (cf. VII, 9)

which enable us to reduce a higher power to lower powers with

a small error. In particular, the third Chebyshev polynomial

![$ [ 0 , 1 ]$](img132.png) gives

gives

. The original cubic

is thus reducible to a quadratic with an error not exceeding

. The original cubic

is thus reducible to a quadratic with an error not exceeding

.

.

.

.

![$\displaystyle \vdots \makebox[0.9\textwidth][1pt]{\ } $](img142.png)

the coefficient

of the cubic term is annihilated. Then an auxiliary cubic equation

is solved. The roots of the original equation are constructed with

the help of the three roots of the auxiliary cubic. Numerically

this method is lengthy and cumbersome. The following modification

of the traditional procedure yields the four roots of an arbitrary

quartic equation with real coefficients on the basis of a quick

and numerically convenient scheme.

the coefficient

of the cubic term is annihilated. Then an auxiliary cubic equation

is solved. The roots of the original equation are constructed with

the help of the three roots of the auxiliary cubic. Numerically

this method is lengthy and cumbersome. The following modification

of the traditional procedure yields the four roots of an arbitrary

quartic equation with real coefficients on the basis of a quick

and numerically convenient scheme.

.

. are real, the new coefficients are also real.

Hence the original equation becomes solvable in the form of the

quadratic equation

are real, the new coefficients are also real.

Hence the original equation becomes solvable in the form of the

quadratic equation

, a positive real root

must exist. We determine this root according to the method of § 3.

In order to avoid later corrections, it is advisable to add at this point

Newton's correction (cf. § 5), obtaining

, a positive real root

must exist. We determine this root according to the method of § 3.

In order to avoid later corrections, it is advisable to add at this point

Newton's correction (cf. § 5), obtaining  with great accuracy.

The coefficients of the reduced equation are then determined as follows:

with great accuracy.

The coefficients of the reduced equation are then determined as follows: