|

|

|

| Random boundary condition for low-frequency wave propagation |  |

![[pdf]](icons/pdf.png) |

Next: Examples

Up: Shen and Clapp: Random

Previous: Introduction

Randomness in a velocity boundary has different effects at different temporal frequencies. Because lower-frequency signals have longer wavelengths, the averaging effect within the dominant wavelength makes the same random boundary appear less random than at higher frequencies. This can be easily understood by taking the extreme case; zero frequency has infinite wavelength, so it sees a random boundary as a constant velocity, no matter what velocity distribution is used. For a random velocity field to appear random to a low-frequency signal, a coarser ``grain'' of random velocity anomalies is necessary. If grains are bigger than a single cell, two adjustable parameters become important in determining the effectiveness of such random boundaries.

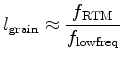

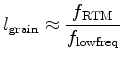

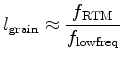

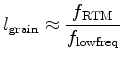

The first parameter is the size of grains. A simple way to determine the grain size is:

|

(1) |

where  is the effective length of the random velocity grain,

is the effective length of the random velocity grain,  is the dominant frequency in the RTM that uses the random boundary condition, and

is the dominant frequency in the RTM that uses the random boundary condition, and

is the dominant low frequency used in modeling. The above equation holds because of the inverse relationship between frequency and wavelength at a given velocity. The second parameter is the shape of grains, the easiest to implement of which is cubic, with side lengths equal to the effective length

is the dominant low frequency used in modeling. The above equation holds because of the inverse relationship between frequency and wavelength at a given velocity. The second parameter is the shape of grains, the easiest to implement of which is cubic, with side lengths equal to the effective length  . Although this works much better than a single-cell random velocity anomaly, its effectiveness is diminished by its regular shape. To further increase the randomness of reflected and scattered wavefields, we propose randomly shaped grains in place of cubic grains. We generate randomly shaped grains by perturbing cubic grains of certain lengths. In this case, the effective length of such a randomly shaped grain is equal the the side length of the cubic grain being perturbed. The perturbed grains will have similar volume or grain size to the cubic grains, but have random shapes that more effectively scatter coherent wavefields. It will be shown next that randomly shaped grains also work well with higher-frequency signals, because the irregular, small-scale features at grain boundaries scatter shorter wavelengths effectively.

. Although this works much better than a single-cell random velocity anomaly, its effectiveness is diminished by its regular shape. To further increase the randomness of reflected and scattered wavefields, we propose randomly shaped grains in place of cubic grains. We generate randomly shaped grains by perturbing cubic grains of certain lengths. In this case, the effective length of such a randomly shaped grain is equal the the side length of the cubic grain being perturbed. The perturbed grains will have similar volume or grain size to the cubic grains, but have random shapes that more effectively scatter coherent wavefields. It will be shown next that randomly shaped grains also work well with higher-frequency signals, because the irregular, small-scale features at grain boundaries scatter shorter wavelengths effectively.

|

|

|

| Random boundary condition for low-frequency wave propagation |  |

![[pdf]](icons/pdf.png) |

Next: Examples

Up: Shen and Clapp: Random

Previous: Introduction

2011-05-24

is the effective length of the random velocity grain,

is the effective length of the random velocity grain,  . Although this works much better than a single-cell random velocity anomaly, its effectiveness is diminished by its regular shape. To further increase the randomness of reflected and scattered wavefields, we propose randomly shaped grains in place of cubic grains. We generate randomly shaped grains by perturbing cubic grains of certain lengths. In this case, the effective length of such a randomly shaped grain is equal the the side length of the cubic grain being perturbed. The perturbed grains will have similar volume or grain size to the cubic grains, but have random shapes that more effectively scatter coherent wavefields. It will be shown next that randomly shaped grains also work well with higher-frequency signals, because the irregular, small-scale features at grain boundaries scatter shorter wavelengths effectively.

. Although this works much better than a single-cell random velocity anomaly, its effectiveness is diminished by its regular shape. To further increase the randomness of reflected and scattered wavefields, we propose randomly shaped grains in place of cubic grains. We generate randomly shaped grains by perturbing cubic grains of certain lengths. In this case, the effective length of such a randomly shaped grain is equal the the side length of the cubic grain being perturbed. The perturbed grains will have similar volume or grain size to the cubic grains, but have random shapes that more effectively scatter coherent wavefields. It will be shown next that randomly shaped grains also work well with higher-frequency signals, because the irregular, small-scale features at grain boundaries scatter shorter wavelengths effectively.